If I had to be on a desert island with just three words, they would be patience, acceptance, and gratitude.

Alex Chmeil

It’s very important that I love stumpy.

Patch Adams, referring to his amputated leg

A few years back, I read a tome called Existential Psychotherapy by Irvin Yalom. Though I thought I understood it at the time, the book’s message is only just now starting to sink in.

Here’s what I took from the book, in my own words:

If you want to order “life” from the menu, it will have various ingredients that are painful and unavoidable.

It’s natural to want to get rid of these ingredients, to deny that these are parts of life. In the short-term, denial strategies can reduce pain. In the long-term, they can lead to suffering and can block flourishing in life.

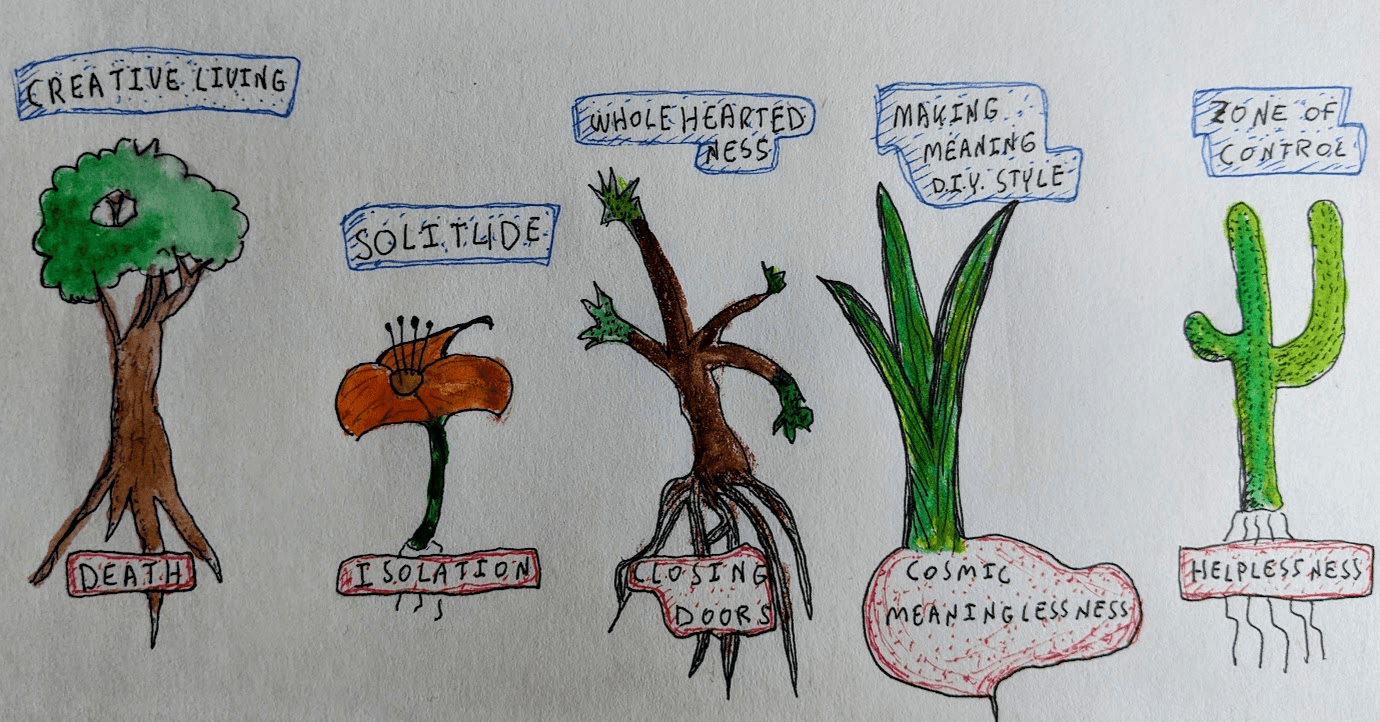

As I see it, here are some painful and unavoidable ingredients of life:

- Death, the fact that we have limited time to play here on earth*

- The fact that we cannot do everything, that in choosing what we fill our life with, we need to close many doors

- Existential isolation, the fact that we are the only person who can experience our own consciousness*

- The lack of an external, cosmic meaning to life*

- Our helplessness to change many things in the world

*If you believe in a religion, you may believe that you will have eternal life, that God knows you, and also provides an external, cosmic source of meaning. I am an agnostic without strong faith in God, so these hold for me.

These ingredients may sound depressing, but there’s an upside to them: each has a corresponding skill that can make you better at the art of living. You can see each of these skills as a beautiful plant that grows out of life’s pain.

In the rest of this post, I’ll take you through my own personal journey towards acceptance of each of these painful facts, and growing a garden of plants that transform their pain into beauty.

There’s a video of Patch Adams talking about having fun with his amputated leg, which he calls “Stumpy.” Patch says that we have a choice to lament the negative, or to have fun with it. While I think that at times this perspective can be unrealistic (grief is normal and shouldn’t be bypassed), it’s helpful to say to myself: these facts of life are not 100% terrible. I can adapt to them and my life can be richer and more fun for it!

My journey towards acceptance of these painful facts, and growing helpful plants out of their compost, has been long and winding. This post is long and winding, too. It’s the longest and most detailed article I’ve ever written on this blog.

It’s been a lot of fun reflecting on stories from the different decades in my life, and seeing how far I’ve come. I that hope reading it will somehow be useful to you, in your own life.

ROADMAP | Five plants (skills) that grow from life’s painful facts

- Acceptance of death, and using an awareness of our limited time as a stimulant for creative living

- Wholeheartedness

- Solitude (and knowing others)

- Making meaning, D.I.Y.-style

- Knowing your zone of control

Plant #1: Acceptance of death, and using awareness of our limited time as a stimulant for creative living

Not to live as if you had endless years ahead of you. Death overshadows you. While you’re alive and able — be good.

Marcus Aurelius

I have seen death in life’s pattern and affirmed it consciously. I am not afraid to live because I feel that death has a part in the process of my being.

An individual after a sudden illness, Existential Psychotherapy

When I turned 20, I hit peak existential crisis on a college ski trip to Mt. Tremblant. The trip was supposed to be a fun time, skiing and hanging out with a bunch of my classmates. We bought alcohol, food, fancy cheese. We played drinking games. We hit the clubs in town.

I remember one night in particular. We made each hotel room into a station for a different drinking game. After already drinking a lot in several of the rooms, I arrived at a room which was called “crab wrestling.” I put my four limbs through the arm holes of an oversized T-shirt, which limited my motion, turning me into a human crab.

“One, two, three, go!” exclaimed the referee, and the wrestling match began.

I was hot and uncoordinated, and the enemy crab pinned me down quickly. I lost, and had to drink. But something about that drink was too much for me. I felt waves of nausea coming, ran to the toilet, and threw up.

As I was vomitting, dark questions flooded through my mind. Why did I drink so much? Why couldn’t I connect with anyone here? Why were these activities that were supposed to be fun — skiing and games — so utterly meaningless?

Back on campus, life wasn’t better. Typical activities included watching a movie with 40 oz bottles of beer duct-taped to my hands and having to drink both before I could go to the bathroom (you couldn’t unzip your pants with the full bottles taped to them, and pouring out the beer was against the rules). Or going to a parties with loud music, booze, and the implicit objective to hook up. I desperately wanted to belong, to connect, but these standard-issue activities just made me feel more alone. Everybody was making sarcastic jokes, nobody was talking about what really mattered.

I escaped college by studying abroad in Australia. I loved being close to nature, being physically active, and all the unfamiliar fruits and insects and animals. But still, something was off. I would look at myself in the mirror and see wrinkles forming on my face, sharp valles cutting through the sides of my mouth. I am getting old, I thought. This is not right!

At an all night party in a club with new Australian friends, I remember thinking to myself: what is the point of all this dancing? These people will soon be skeletons. They are wasting their time.

Then, another thought came to me: I’ll find a way out of death. Other people will become skeletons, but not me. I won’t fritter away my time with parties. I will work hard, on scientific research, so that I do not age, so that I do not die.

Aha! Went my brain. In that moment, my life’s purpose became clear: I will cure aging.

“Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal‟ had always seemed to him correct as applied to Caius but certainly not as applied to himself…Had Caius kissed his mother’s hand like that, and did the silk of her dress rustle so for Caius?

Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Illych

I changed my major to biology. For my senior thesis, I studied the molecular biology of aging. After graduation, I attended a conference called Ending Aging run by an eccentric British guy with a long black beard named Aubrey DeGrey.

The conference was a smorgasbord. There were caloric restriction enthusiasts there, super skinny folks who spoke in weak, half-alive voices. There were people hucking supplements. Some people who wore medical bracelets from the cryonics company Alcor, so that if they died, their heads or whole bodies could be quickly frozen.

There were plenty of legit scientists there too, but something about the general vibe was off. I got a job offer to work with DeGrey’s organization on research to clean up intracellular debris, one of the causes of aging. I considered it, but didn’t take the plunge. Instead, I volunteered at a tissue engineering lab at the University at Buffalo, and spent seven months trying to grow blood vessels using stem cells. This experiece made me understand that despite the hype in the news about stem cells, growing a structure even as simple as a blood vessel was no easy task.

I read a book called For the Love of Enzymes, an autobiography of Arthur Kornberg, the scientist who discovered DNA polymerase. This book got me interested in basic biochemistry, and inspired me to start a year-long research program at the NIH.

I was very idealistic about research. At one point, my lab wanted to fly me out to a conference in New Orleans. Though I wanted to go, I felt bad that the lab would spend money on me when I wasn’t presenting any original research at the conference. Though my lab would pay for my hotel stay, I chose to stay with an acquaintance from college for five days. This was not convenient for either of us, but I wanted to save the NIH money, so they could fund more valuable research that would one day cure aging.

As my year at the NIH drew to a close, my idealism waned. I realized that on a day-to-day level, most scientists were focused on building their careers, publishing the next paper. Whether aging would ever be cured, or not, was not clear to me, but it certainly seemed extremely far off, much, much farther than I previously thought. I decided to go into medicine, to see what healing people in the here and now was all about (as opposed to in the science-fiction future).

During my first summer off from medical school, my enthusiasm for research continued to fade. I got a job in a neuroscience lab that studied information processing in the retina. Part of my labwork involved beheading tiger salamanders, and meticulously dissecting and analyzing their retinal tissue. I became a vegetarian, to balance out the karma.

The retina is a “model system” for neural information processing. It has seven clear layers, and is a very simple structure compared to the brain.

But it is by no means simple. Here is a diagram of the retina:

As you are reading this post, light from the computer screen is stimulating your photoreceptors and causing them to fire. Next, the information in the firing pattern of the 100 million photoreceptor cells is transmitted through the seven layers of your retina to 1 million ganglion cells that feed into your brain. In the process of this transmission, the information is coded. Our lab was studying this coding process.

Working alongside experts in the field, I realized that science of how the retina processes information is very early-stage. The ultimate goal of the research was to be able take recordings from the ganglion cells, and reconstruct the image that the retina saw. We were nowhere close to being able to do this. And the retina is a far simpler system than the brain as a whole.

The more time I spent in science and medicine, the more I saw that the brain is an intricate three-dimensional work of art. An effective anti-aging therapy would have to do in-the-moment art restoration on this intricate and delicate sculpture. I saw that this would be really, really hard. So hard, in fact, that it would be delusional for me to build my life on the idea that I would become immortal. I thought: given the track record of my fellow humans, it’s more realistic to change my life plans to include dying.

Don’t get me wrong, I’ve seen amazing things in my medical journey: using a virus to cure a genetic disease, using engineered T-cells to fight cancer. But solving aging isn’t about fixing a single discrete problem, it’s about augmenting our cellular repair systems, throughout our whole body and especially our brains. This is a problem of much greater scale than anything medicine has done up to this point.

In my early 20s, I was mesmerized by Aubrey DeGrey’s concept of “escape velocity” — reaching a point where successive rounds of biomedical breakthroughs will lead to immortality. In my mid-30s, I am less enamored with this idea. In my neurology practice, I see patients with brains breaking down from neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and I have few truly effective therapies to offer them. When I think back to my time in the lab, I realize that it’s no wonder that we don’t have disease-modifying treatments for neurodegeneration: the brain is really, really complicated. “Escape-velocity” sounded plausible to me fifteen years ago, when I knew little about the brain. Now it sounds like pie-in-the-sky thinking.

And even if aging were no more, the chance of death would never be zero. Accidents and diseases could still get you. Really prioritizing not dying would keep me in a chrysalis: always vigilantly focused on myself and the health of my body. I think that this relentless self-focus would not be psychologically or spiritually healthy. The past few years, I’ve been asking myself the question: “What is a good life?” The answer I’ve come to is that a good life requires not just self-focus, but a focus on others too.

Laura Huxley, who is a very dear friend, in her kitchen has these jars over the sink, and she takes old beet greens and orange peels and things and sticks them in the water on these long, beautiful pharmaceutical jars. Then they slowly start to mold and decay, and there are these beautiful decaying formations of mold. It’s really garbage… it’s garbage as art. We look at it and it’s absolutely beautiful…I’ve begun to expand my awareness to be able to look at the universe as it is, and see what is called the horrible beauty of it. I mean, there’s horror and beauty in all of it, because there is also decay and death in all of it. I mean, we’re all decaying – I look at my hand and it’s decaying. It’s beautiful and horrible at the same time, and I just live with that.

Ram Dass

For the last two years, I went to an event called Wonder Wander, which I tremendously enjoyed. This year, I didn’t go. In a way, not going to Wonder Wander was like dying. I watched a video of the event, saw the party of life going on without me.

People were connecting, falling in love, planning trips together, as I once had. It was kind of like going back to your college campus, and seeing fresh batches of faces, doing the same things that you once did, many years ago. Life keeps spinning, I saw, without me.

I created a legacy project for the Wonder Wanderers, so there was a way for me to contribute to the event even though I was not there. But my literal presence was missing. In a similar way, at some point in the future, my presence at the party of life will be no more, and all that will be left are the ripples of my actions while I was alive.

Lately, as part of my morning routine, I’ve taken to walking to the graveyard near our house. I’ve been reading Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. These things consciously remind me that yes, this will all be over. Soon, I too will be a skeleton. As Marcus says: “One who laid out another for burial, and was buried himself, and then the man who buried him.”

Death acceptance helps me live with greater perspective, courage and vibrancy. Death “trivializes the trivial,” as Irvin Yalom says. Accepting my own death has led me to the central principle of my life: limited time.

I’ve come around to the view that awareness of limited time can infuse life with greater meaning. An artist who has a finite canvas on which to paint will create a better picture than one with an infinite canvas.

In my freshman year of college, I read the book Story, a how-to bible for screenwriters. I still remember this excerpt:

THE PRINCIPLE OF CREATIVE LIMITATION: Limitation is vital…Artists by nature crave freedom, so the principle that the structure/setting relationship restricts creative choices may stir the rebel in you. With a closer look, however, you’ll see that this relationship couldn’t be more positive. The constraint that setting imposes on story design doesn’t inhibit creativity; it inspires it.

Robert McKee, Story

We can look at the limited time we have in our lives as the ultimate creative limitation. Because we don’t have infinite time to do everything, we have to choose wholeheartedly which things (people, places, actions) we fill our time with and do our best to make these choices beautiful.

This brings me to the next crucial skill for life…

Plant #2: Wholeheartness

Opportunities exclude.

John Gardiner

You can’t sit with one butt on two chairs.

Russian Proverb

A good life is saying HELL YES to a few things, no to everything else.

Thomas

You can do anything, but not everything.

David Allen

Sit. Walk. Don’t wobble.

Zen Proverb

What can I be wholehearted about?

David Whyte, 10 questions that have no right to go away

One of the big themes in my life the last few years has been exploration. Through experiences like clowning, living on an ecovillage, and going to Wonder Wander, I’ve broadened my sense of just how big the house of life truly is. A few years ago, I think I saw life more narrowly: with narrow goals and possiblities. Now, I see life as this huge house that has many, many rooms. Infinite rooms, even.

Yet being in such an infinite house, we still have to decide how to spend our finite time. Each quote above points to the same essential truth: by choosing one door, we necessarily exclude others.

We have to choose which rooms we will make our homes, and which rooms we won’t. A wholehearted life is one where you are fully present in the rooms you choose to spend your time, and you fully grieve the rooms you haven’t chosen.

I was hanging out with my friend recently, who said: “You would love social dance.” Yes, perhaps. But at this point, my plate of activities is full and I know I won’t go very deep into this room. Just like I won’t get into coin collecting, or windsurfing.

The pain of closing a door is directly proportional to my mind’s prediction of what lies behind that door. In a self-help seminar with Mark Manson, a caller said that he feels shame that he spent his 20s trying to become a musician and this hasn’t worked out for him. Manson says that yes, shame is part of the story, but also, there’s grief. This guy needs to grieve the loss of his identity as a professional musician.

In middle and high school, I got into magic. Though I stopped pursuing magic seriously in early high-school, I never grieved the loss of my possible future as a magician. Recently, at age 37, I watched a documentary about a professional magician, and got super emotional. I went down a rabbit hole of watching all these magic videos. I was re-connecting with that child in me that loved magic, and wanted to be a magician. Many years after I gave up magic, I grieved closing of the “professional magician” door.

While writing a piece about the documentary, I realized that every life necessarily excludes every other. Just as I have not become a magician, the magician in the documentary has not become a neurologist. A few months ago, I met a retired magazine writer in his late 80s who told me that he’d always wanted to become a doctor. I was living this guy’s dream. Yet eventually, in his life, this man found peace in being a writer, doing good for society by writing about things like the civil rights movement. He wasn’t a doctor, but he was doing a form of healing work too.

Yes, it can be good be be a hyphenate of a few things, but being a zookeeper-farmer-surfer-banjo player-astronaut-coin collector-blacksmith-trail runner-monk-movie director-wall street trader-photographer stops being charming, and smacks of an inability to accept the painful fact that in life, we have to close doors.

Recently, my brother and I spent four days travelling on Kauai. Because we only had four days, there was this pressure to “do it all.” We made ourselves stressed by jam-packing our days, rushing from one activity to the next. After we left Kauai, our time slowed down. We began to have long, slow tea ceremonies in the mornings. When I told my mom about this, she remarked that this was something of a waste of time. I said, “we’ve experienced the alternative.” We’ve experienced trying to do it all, and it was darn stressful. So now, we choose to sit and slowly sip our tea, joyfully missing out on the million other things we could be doing.

Learning how to close doors, then, and grieve the closing, is a necessary thing. My friend Thomas explained to me the difference between grief and wallowing. Grief is a fire that burns hot, and then eventually dies down (though the embers may burn our whole lives). Wallowing is a low-level angst that perpetually smolders. The thing that keeps wallowing alive is fantasy.

If I constantly feel bad that I’m not a magician, but partially believe that some day in the future, I may still be one, then I am wallowing in the angst of a fantasy, I’m living half-heartedly. You can replace “magician” with a relationship, a place to live, a career, anything you wanted at one point, but didn’t materialize. For me, half-hearted living comes from living in one reality, while simultaneously indulging in a fantasy that one day, I will be in a different reality where everything will be great (all the while taking no actions to actually make changes).

I am prone to wallowing, to using fantasy to avoid grief. For many years, I’ve thought about an ex fairly often, and intrusively. What I got out of this fantasy was that I was able to avoid grieving the loss of the relationship. I realized that this was a mental pattern for me not just with this person, but rather it is something I’ve done to some extent for my whole life, starting with a crush in third grade. A crush is all fine and good, but holding onto a fantasy for years and years while doing nothing to pursue it can sap the enjoyment out of life. It seems like my mind loves to produce idealized versions of people and experiences, and then wallow in unfulfilled fantasies.

Recently, I met a guy who practiced Sufism. After the meeting, I fantasized going to the Sufi retreat center he went to and getting into Sufi practice. The belief driving the fantasy about exes and the fantasy of Sufism is the same: that happiness is just around the corner, not here-and-now. The fantasy says: if I just get with this person, or become a practitioner of this religion, then I’ll be in a state of permanent happiness and fulfillment.

Fantasies stay alive because they provide a dysfunctional kind of enjoyment. For a long time, I had a fantasy that life would be better in a warmer climate, compared to New York City. Well, this year, I moved to Hawaii. Now, I’m no longer indulging that fantasy, I am actively testing the hypothesis. I’m living.

I want to get better at spotting when my mind goes into fantasy mode. If there’s a fantasy a-brewing, I have two choices: take steps to make it real, or close the door. The alternative is half-hearted living.

A crucial skill for wholehearted living is closing doors, and grieving their closing. Time and energy are limited. We cannot keep infinite friends, go on infinite trips, pursue infinite careers, marry infinite people, do infinite things with our lives. Choosing to spend time with certain people and do certain activities means we won’t choose other activities and other people. Because those doors not taken are fully closed, they are left in the past, and my attention is freed up to embrace the present moment, the people and experiences before me.

Plant #3: Solitude (and knowing others)

What is the temple of my adult aloneness?

David Whyte, 10 questions that have no right to go away

I did online group therapy a while ago, and the biggest epiphany for me was a single moment when a woman in the group said: “I’m afraid of being alone.”

Holy crap! I thought. Me too!

Her putting this fear into words made me realize how similar we humans are, and how we all want connection.

In elementary and middle school, I was bullied. This led me to develop a belief that social connection was a limited resource. Achieving a connection was, for me, a rarity. It just didn’t happen all that often, and when it happened, I got clingy.

The pinnacle of my social life was getting a ride to a party after a big dance at my high school. This party was an hour away, at a big house in a ski town. The kids at this party were all “cool” and they were drinking, smoking weed, hooking up. No one expected to see me, a non-cool kid, there.

People gave me lots of attention and warmth. At one point, I did keg stands to cheering onlookers. At the end of the party, I felt great. I felt like I made a big social breakthrough. Back at school, I had earned a reputation. “I heard you did keg stands,” people said.

But nothing fundamentally changed. In a week or so, my 5 minutes of fame ended, and I did not get invited to any more parties. Why?

I think it was my mindset. I was seeing social connection as scarce, and so, I was clingy. I would send people hundreds of messages AOL instant messanges, trying to penetrate their social spheres. Few people sent me messages back. Fundamentally, I was trying to fit in with the wrong people. If I could go back in time, I would stop worrying about “being cool” and just try to form meaningful connections with whoever wanted to connect with me. My senior year of high school, I did just that, and this was the best year of my life.

People say high school is never over, and I think that’s true. At the rock climbing gym the other day, I said hello to a guy. He said hi back. We exchanged names. I watched him climb a route and gave him a compliment.

“I’m going to try that route,” I said.

“It’s a lot of fun,” he said, but there was something not-quite-warm about his energy. I was confused about how to respond. Seeing that he was walking past me, I thought that maybe he was leaving.

“Have a great day!” I blurted, then saw: he wasn’t leaving, he was going to climb another route. He stared at me, confused.

In that moment, I felt like my high-school self again, desperately wanting to connect, to get invited to the party with the cool kids. Then, I gave myself a pep-talk: I have the skills to connect with people, and have done this countless times before. I’ve entered into situations where I have known nobody, and have made meaningful connections with new humans. I got this!

Then, I went to a different part of the gym, and struck up a nice conversation with another guy. We chatted about life for about 20 minutes, and collaborated on a route. My confidence in my ability to connect was restored.

In my life, I’ve found myself feeling like that lonely high-school kid more often than I care to admit. When I think back to the last eight years I spent living in New York City, despite having friends and romantic partners, I frequently found myself feeling lonely. This song lyric captures my emotional landscape during those moments:

And back when I was 12 or so I swear to god I never felt so low

Jeffrey Lewis, Back when I was four

Everyone but me was making out and eating cookies

Recently, I had a experience which gave me further insight into the feeling of loneliness. I spent 6 weeks living by myself, working on the island of Kauai. I came to the island knowing nobody. Over my 6 weeks there, I didn’t have an explicit goal to socialize. Not having this goal let me focus instead on reading books and spending time in nature. Amazingly for the most part, I didn’t feel lonely.

How could that be? How could I feel lonely in NYC, where I had objectively more social connections, and not lonely on Kauai, where, outside of work, I didn’t see many people at all?

I talked to my friend Ethan about loneliness. Ethan did a lot of travelling in his 20s, and this travel put him into situations where he spent lots of time alone. The times when he felt most lonely, he said, were times when everyone else seemed to be getting together, like on Friday nights. I realized that my mind is the same as Ethan’s. If I’m spending a Wednesday evening by myself reading a book, my mind can tell me the story that all is well. But if I’m spending a Friday night or Thanksgiving or Halloween by myself reading a book, then my mind can tell me that I’m a loser and have no friends (the exact words my sixth-grade bully would say to me on the daily).

I realized that loneliness has both a primary and a secondary component. The primary component is what we typically think of as loneliness: missing human interaction. The secondary component is rooted in social comparison. On Kauai, I did not feel the secondary component of loneliness because I did not expect myself to know anyone. Because I’d just arrived on the island, my mind set my social bar low. I did not compare my social wealth to that of others. So, all I experienced on Kauai was the primary component of loneliness. With no friends, family, or romantic partner, I was surprisingly OK. My mind did not torture me with thoughts of being a friendless incel loser. So much of my own loneliness is the secondary component, I realized.

Yes, I got lonely at times on Kauai. But mostly, the solitude was lovely. I had the chance to commune with nature, read, self-reflect, and think my own thoughts. The experience serves a reference point for me: this is what it feels like to be alone. It’s nothing to fear. I can handle it.

The Kauai experience was also useful for all of my relationships, be they with family, friends, or romantic. Now I can show up to relationships from a place of enough-ness. I’m not grasping at the relationship out of fear of being alone. I’m showing up to the relationship with my cup full, ready to give.

Sometimes, I still notice scraps of clingyness within myself, when I have expectations that people will behave in highly specific ways. I catch myself thinking: “Why didn’t my friend ask me about that.” In these times of constriction, I think back to Kauai, when I communed with the waves, moon, clouds, books, and my own thoughts. At that point, I did not need a friend to ask me a specific question. If I had a painful thought, I learned to be OK holding it.

If you are constantly relying on others to hold your pain, that’s a recipe for clingyness. Yes, we need each other. It’s a lot more fun to not go through life alone, but also, solitude is necessary skill to build because when you are an adult, you won’t always have someone to hold and witness your thoughts and feelings. It’s good to learn to do that for yourself.

When we are children, we rely on good parents to give us a compassionate, loving presence. Growing up is about internalizing this presence, learning to be the loving witness for yourself. In some way, I think I first grew up at age 37, while living alone on the island of Kauai.

I remember when I was a kid, when I played violin, I’d make my parents and grandparents watch me play. I needed the audience. I was clingy. Now, while it still feels good to have an audience, to be witnessed, I hope that I’m a little less dependant on the eyeballs. I can acknowledge and enjoy the experience of being seen, and be grateful for this attention, but I don’t crave or cling to this experience, since I’m able to be the witness for myself. And because I know how good this experience is, I can be the loving witness for others.

There’s a central paradox of life: to be truly good company for others (and not clinging to them to fill a lonely hole in myself), I need to practice spending intentional, voluntary time alone. As Kevin Kelly says, “If I don’t accept an invitation, please understand that saying no is the only way I can preserve some time to create something interesting to say when I do say yes.”

Since coming back from Kauai, I’ve integrated the experience by going on walks by myself, going to art galleries by myself, swimming by myself, reading, writing. These intentional experiences of solitude are reminders that yes, I’m OK with my own own company.

Solitude is not only not the end of the world, it’s pretty awesome. In solitude, the greatest connection with creativity, my thoughts, nature and the universe happens for me. In solitude, I strengthen my ability to be the loving presence for myself. Solitude helps fill my cup, so that when I meet another person, I have something to contribute.

Thinking back to the “fear of being alone” voiced by the woman in my therapy group, it seems that the only way out of this fear is through: to see what solitude feels like, and realize it’s nothing to fear.

Plant #4: Making meaning, D.I.Y.-Style

For a long time, I subscribed to the idea that meaning in life would come to me from certain external accomplishments. If I had kids, or had a certain career or believed in a certain religion, then a package labelled MEANING would be delivered in the mail. I would look at people who seemed to have gotten this package with jealousy. When was mine coming?

But then I realized that each of the common sources of meaning — parenting, career, religion — is not 100% reliable:

- There are parents who find the project of raising their children to be meaningful uses of their time on earth. Other parents resent this role: they are absent from their children’s lives or are downright abusive.

- I had a friend in high school with great passion for computer science. Later in life, I met software engineers who envied my work as a doctor. They found little meaning in their work, and imagined mine to have great meaning.

- While visiting Israel, I met an Orthodox Jewish Rabbi who seemed to have a great sense of meaning in his faith-based life. He had done much seeking in his youth, and landed on his spiritual home in Orthodox Judaism. Later, I met people born into Orthodox Jewish communities who have left them, for various reasons.

Recently, I had a conversation with a friend who is divorced. Years ago, when he was married, I looked at his life from the outside and thought: wow, he has found meaning. During our recent conversation, my friend revealed to me that his marriage was based on fear and jealousy. Looking in from the outside, what I percieved to be meaning was not what he was in fact experiencing.

Ultimately, meaning is subjective. It’s based on our perspective and the stories we tell. For instance, if I spend my life treating patients with a certain drug thinking that it is helping them, and then at the end of my career it turns out that the drug was actually harmful, then my source of meaning might implode on me.

I started watching a YouTube channel called Soft White Underbelly, created by a photographer who worked his whole life in advertising and then pivoted to use his skills to tell stories that create empathy. This photographer found the legacy he’d created as a commercial photographer not meaningful enough, and is now working in a different area, to create more meaning.

I recently spoke with a cafe owner who worked in her 20s selling luxury jewelry, then asked herself: “What am I doing?” In her second act, she opened a cafe to give people a respite from the hustle and bustle of New York City, a space to be creative and productive. This pursuit gives her meaning now. In the future, her perspective might change again and a different source of meaning might emerge in her life.

Meaning is D.I.Y. The only sure-fire source of meaning, really, is the meaning we create ourselves. After working as a doctor for a few years, I have a few stories of meaning I can remind myself of: patients who I think I really helped though my medical skills. For example, I have several patients who came to my office with severe cognitive problems, who after treatment are cognitively normal. I find thinking about these patients to be particularly meaningful.

I have another source of meaning in medicine: providing education and emotional support to my patients. One of my first mentors in medicine told me before I started medical school: “Remember, every patient who walks into your office is scared.” When I remember this, I have a greater sense of empathy and meaning. My patient who reads “white matter disease” on an MRI report and gets worried becomes someone I can help, rather than an irksome person wasting my time. It’s my choice which of these two meanings I give to my patient, and I strive to choose the first.

Two broad sources of meaning for me are growth and service. For example, there is a simple Tibetan prayer that I have been saying before meditation practice: may this practice be for the benefit of all beings, may it help me not do harm, to help others, and to purify my thoughts, speech, and actions. This framing gives a clear why to my practice: for personal growth, and for service.

Another example is at work, I hung up a post-it note with my mission statement on my computer monitor: I fix people’s brains (and spinal cords and nerves) when I can, and otherwise empower people with support and education. Having this visual reminder of my why helps me come back to a meaningful narrative in my mind, when I’m lost in the weeds of something small or frustrating, like calling an insurance company to get an MRI approved.

A third example is writing. Why am I spending many hours writing this long post? In a podcast interview, Kevin Kelly said, “I don’t actually know what I think until I try and write it. Writing is a way for me to find out what I think…When I write, I get the ideas. That was the revelation.” I couldn’t agree more. In the process of coming back to this post, day after day, many ideas new ideas and understandings about life have emerged for me. So my why for writing is: I write to find out what I think, and to make meaning out of my life.

Ultimately, meaning comes down to my why for doing something, to my values. To be meaningful to me, I have to be able to see how the things I fill my time with are in service of others or help me grow in some way, or both.

Plant #5: Knowing your zone of control

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

Serenity prayer

More than many years ago when fewer things had happened in the world and there was less to know, there lived a young man named Alberic who knew nothing at all. Well, almost nothing, or depending on your generosity of spirit, hardly anything, for he could hitch an ox and plow a furrow straight or thatch a roof or hone his scythe until the edge was bright and sharp or tell by a sniff of the breeze what the day would bring or with a glance when a grape was sweet and ready. But these are only the things he had to know to live or couldn’t help knowing by living and are, as you may have discovered, rarely accounted as knowledge.

Alberic the Wise, Norman Juster

For the past few weeks, I’ve been trying out a subscription to the New York Times. And, the more I’ve read the paper, the more I’ve become aware of problems in the world. Last night, I awoke at 4am, unable to turn off my brain. Is World War III coming? my anxious mental voice asked.

This was enough for me. I unsubscribed from the New York Times. This felt good. All that obsessive reading I was doing wasn’t changing the world one lick.

I sometimes wish I could take all of humanity by the shoulders and just shake some sense into them. “Can you stop being such damned fools, for a change!” I yell, in my fantasy.

Alas, the shaking solution isn’t a real fix for our problems. We have to solve them the hard way, one by one.

In my travels and friendships over the years, I’ve met what Mr. Rogers calls helpers, people who are working to combat each of the above issues. The thing I’m realizing is that each individual person can only do so much.

When I was younger, I thought that my ability to change the world was greater than it actually was. I was really into recycling, and my dad wasn’t, so I would zealously move things from the trash to the recycle bin. Items as small as post-it notes.

Now, after being in the world longer, I realize that everything takes energy and attention. I worked in a medical office that did not recycle. In three-and-a-half years of working there, I’m not proud to say, I didn’t try to change the recycling system. I did not prioritize doing this, amid all the other responsibilities I had.

When my dad was putting recyclable things in the trash, you could say he was lazy, but you could also say he had limited bandwidth and was probably juggling a million things like bills, work, groceries, relationships, and fixing things around the house. Recycling just wasn’t a priority. Me, a kid who had all my meals provided for, had the bandwidth to get righteously indignant about the recycling.

And, years later, I learned that a lot of recycling wasn’t effective anyways. A crisis of meaning if ever there was (see the previous section).

On one of our first meetings, my therapist told me the serenity prayer. Lately, as an adult increasingly aware of our messy world, I am looking it anew. I can scroll the newspaper ad nauseum, but what am I going to do about the messiness? As individuals, our capacity to repair the world is quite small.

I think of society as a big ship headed for rocks. There are swimmers in the water pushing the ship away from the rocks. These are the helpers. There are other swimmers pushing the ship towards the rocks, the people playing the games of hate and power and greed.

Which swimmers are we? If we’re being honest, probably both, at different moments in our lives.

In the past, I’ve despaired that I cannot fix all of the world’s problems. But lately, I’ve come to see that we are all quite small. I have friends who are doctors, other friends into public health, or doing work combating racism. Others are into reforming our prisons, or organic farming.

Each of us can only do so much. Yes, some swimmers may be stronger than others. Elon Musk or Paul Hawken or Greta Thunberg are doing more to fight climate change than me, but they aren’t doing as much for people with neurological diseases. MLK did more for civil rights than I’ll ever do. But as much as we venerate MLK, he was part of a lineage of civil rights activists, and the civil rights accomplishments society has made are thanks to people who worked before, alongside, and after him. Even the major players of history are still just grains of sand in the grand human drama.

Marcus Aurelius, the most powerful man in the world at the time, reminded himself of his smallness frequently: how soon he’d be forgotten in the sands of time, how he was just a stick figure compared to the vastness of nature.

Kimya Dawson puts it well:

Rock and roll is fun but if you ever hear someone Say you are huge, look at the moon, look at the stars, look at the sun Look at the ocean and the desert and the mountains and the sky Say I am just a speck of dust inside a giant's eye

The serenity prayer is really, I think, about seeing our true scale. Can we solve the world’s problems? No. Can we contribute a little bit? Yes.

Can we be kinder with the people in our lives? Can we give more grace to ourselves? Yes and yes.

Start there.

Concluding words

Though I’ll never “master” these five skills, I hope that I’ll get better at them through practice. Every day is an opportunity to live with more wholeheartedness, meaning and creativity in the limited time I have on this planet. Every day has opportunities for both solitude, and seeing others deeply. Every day is a chance to get clearer about what I can change in my life and the world, and what I can let go of worrying about.

I hope that these words have been as useful for you to read as they’ve been for me to write. Sending you all my love in your own journey towards a good life.

Edith Eger said, “Write a book about your life. Don’t keep it in your head.” It was cathartic to write about my life at length here. Thank you for reading!