Universe bloom

We are small in time and space

But how to see it

How to really feel it?

How to infuse the medicine

Of my smallness

Into my veins?

Copernicus told us we're not the center

But still

We feel like we are

Today --

The sweeping of the floor

The chopping of the vegetables

The "have to do's"

Today --

Is best approached

Not from a yarn

Of "not enough":

"Not enough time

Not clean enough

Late..."

But from the lens of rareness

How rare is a messy apartment

As a form

Among the milky way?

Rarer still, among the universe

Planet earth

Is a rare grapevine

Hanging

In the great empty

Where these rare fruits

Messy apartments

Can be found

"Clean your room"

Is good enough advice

As long as we don't forget

To take stock

And have awe

As good Mr. Sagan reminds

A messy apartment

Is like a delicate cactus bloom

Here today

Another might not come

For a billion years and miles

In the great expanse

The earth is a cactus bloom

In the universe desert

Messy apartment or not

I'll take it

All of it

Yes/

Category: Uncategorized

No different from the banana tree

No different from the banana tree

Streaks of grey in my hair

Wrinkes on my face

Chips in my teeth

Turning yellow

Planted a banana tree

And now, a year later, it's dead

But dozens of keiki

Are growing

All around

I used to lament

The wrinkles and the grey

The tooth decay

"We love to forget

about impermance"

Says my friend

A teenager at the dance

Says I'm strong like a tree

"I don't think of myself as strong"

I say

I guess I'm strong

I've filled out the spaces

Between my bones

With muscle and fat

No longer thin

Like I used to be

I guess I'm strong

Like a tree

For now

A refreshing lack of importance

What if mountain goat

Took a note

From Sapien

And strove towards

The magazine cover?

What if wildflower

Built a tower

And strove to climb

To the top?

The city of field, forest, stream, and mountain

Whispered in my ear:

“You are no more or less important

Than a wildflower”

It was a refreshing

Lack of importance

(inspired by time spent hiking in silence in Glacier National Park)

sex and stars

sex

makes me think of

the stars surrounding

our pale blue planet

in all directions

sex

makes me think of

the lonely possibility

that another pair of eyes

will grow up here

gazing out at it all

Ode to the unambitious

The arrow of your life is not locked, yet

Thoughts within your mind still freely swim

The key to make you speed has not been turned, yet

You look up at the tall plants as a seed

You have not been pressure-packed and shipped, yet

There is no single place you want to be

Wishes that stream out from you have not been capped, yet

There is no need for practicality

You stand above the helpless souls

Who kick their way to some small goal

My friend, you watch the arrow sway

And delight at the directions

Landlocked canoe

While paddleboarding in the ocean today, a metaphor came to mind. Authentic living = knowing yourself and being in the world in a way that fits your soul.

For example, a canoe belongs in the water. A snowmobile belongs on the snow. A bike belongs on land.

Yet, some of us are born as canoes on land. It might take us a lot of time — decades, even — to find our way to the water. The people around us might say: there’s something wrong with you. You need to change.

But really, what needs to happen is self-acceptance and taking action. If a canoe is born into a family of bikes in a place far from water, it needs to go on a journey. It needs to try a lot of different things. Meet a lot of different folks. And eventually, dip into the water and exclaim: “This is for me!”

Growing up, I felt like that landlocked canoe. I grew up in Buffalo, NY. People around me loved watching sports, specifically the Buffalo Bills and Sabres. I didn’t seem to be able to get myself to care about watching sports.

I recently talked to some friends and asked them: do you like watching sports? They didn’t.

This was healing for me. I realized: I don’t have to force myself to like watching sports. There’s so many other ways I can be in the world. There are people with interests outside of sports I can befriend.

I don’t have to be the canoe who keeps trying to make life work on the land. I can go on a journey and get myself to the water.

Tonight I’m scheduled to have a meeting with someone whose website I found by googling the term “existential depression.” This website defines existential depression as depression arising out of confronting issues like: meaning of life, isolation, death, and one’s place in the world.

I’d never heard the words “existential” and “depression” linked together until I came upon the term in a book about physician suicide. Though I’m definitely a newbie when it comes to learning about existential depression, I resonate with the term.

I think I’ve experienced it in the past several times:

- I’ve felt deeply sad that the people who I loved and loved me would die. I began writing a novel to get humanity to “wake up” the the horror of aging and death and work to solve this problem. Why were we wasting our lives on hedonism when we could work to end aging? After reading my book, I wanted people to get off their butts and get into a biology lab!

- I felt deeply sad that nature was being destroyed by humans, and that, as a human in “the grid” of extractive capitalism, I was part of the problem.

- I’ve felt deeply sad when I was about to turn 20. While studying abroad in Australia, I saw the wrinkles forming on my face as evidence that I was aging and that, if I didn’t do something, I would die and my consciousness would end. I didn’t see the point of having fun times and dancing with my new friends when we’d all be skeletons in the future anyways.

- I’ve felt lonely because I couldn’t seem to fit in throughout most of my upbringing. Growing up, I frequently felt like a weirdo, a misfit. I felt a profound sense of isolation. At one point in childhood, I remember talking to my fish, a beautiful rainbow shark, and telling him: “You are the only one who understands me.”

- I learned how to socially blend in. In prioritizing fitting in, I lost the thread of my true interests. Taking a sabbatical to do clowning and go to an ecovillage, doing the Artist’s Way, going to Wonder Wander, starting reading again, and building local community with people who I resonate with and accept me have been ways I’ve rediscovered authentic connection with myself and others.

- I yearned for a grand meaning that would organize my life, like Orthodox Jews seemed to have (e.g. “Life is about having a family and following the 613 mitzvot”). I yearned for a template that would tell me how to live. Without such a template, I felt massive confusion about all the different possible future paths.

- I’ve experienced tremendous decision paralysis and anxiety at major life crossroads. The core fear I think was an unwillingness to accept that my possibilities will shrink, as the white pages of my future become filled with the text of my life story. Senior year of high school, before going to college, I spent my time going to grad parties and socializing. I basked in the beautiful energy of possibility mixed with belonging. I wrote this poem which describes that feeling. I wanted to stay in that feeling, and yet, my soul knew that I couldn’t. As Neil Young sings: “You can’t be twenty on Sugar Mountain.” These big life decisions were life’s way of kicking me out of Sugar Mountain. On one level, I was paralyzed at crossroads because of perfectionism: I wanted to get the decision “right.” But subconsciously maybe I was stalling because I would prefer to not write the next chapter of my story. I’d prefer to stay undifferentiated…

I don’t have much of an agenda about tonight’s meeting. I’m showing up from a place of curiosity. Writing this has already been healing, and I’m excited about following the breadcrumbs and seeing where they lead!

Very much not root cause

"I'm having a lot of forgetfulness.

It's hard to recall facts.

I'm nervous and twitchy and drooling and dizzy.

It feels like I want to pass out."

Says the man in the rectangle on my screen.

He's on 8 different medications

That affect the brain

5 of them have significant interactions

I'm one of 4 doctors managing the meds

In addition to me, the neurologist

There's the pain doctor, the psychiatrist, the primary doctor

He's in his sixties and weighs over 300 pounds

I wonder

If he'd be better off

Off all the meds

I wonder

Why I feel so heavy

At the end of the visit

I tell him

To reduce the dose

Of two of the meds

***

Last night

My wife and I

Watched a documentary

About the history

Of China

People in history

Were not very kind

***

Part of growing up

I think

Is accepting

That the world we live in

Is the world we live in

And figuring out

Our right size

In it all

Helping but

Realizing the limits

Of my energy

A part of growing up is grief

Grief that the world

Isn't as beautiful

As it could be

Grief that my ability

To change the world

Isn't as great

As I wish it were

My intervention

Of helping the man with his meds

Is very much not the intervention

I'd like to have

I'd like to move him

Into a community

Close to friends

Close to the earth

Where he can express his gifts

Where he can sing

I feel heavy

Because of grief right now

It feels futile

To be spending my time like this

Working on things

That are very much

Not root cause

First I grieve

Then I accept

Then, eventually

I go back to work

Finding names for things

After driving home from work in New Jersey back to the Bronx, I would often feel an impulse to go hang out at An Beal Bocht, our neighborhood Irish Pub. Over the years, An Beal grew to be my favorite bar in the whole world.

I didn’t know why I was drawn to An Beal, but it just felt stifling to go directly from work box to car box to home box. It wasn’t the alcohol I longed for. It was the people, the stories, the decor, the music and dancing, the vibe. An Beal was filled with art, character and characters. Through its frequent live music and open mic nights, theater productions, and just by being a space for all manner of people to gather, An Beal made our neighborhood feel like a community.

Recently, I came upon the term “third space.” This term was coined by sociologist Ray Oldenberg: the first space is the home, the second is work, and a third space is a community space like a coffee shop, church, rock climbing gym, park, or bar, where people can gather. In other cultures, bath houses and saunas serve as third spaces (we have a little bit of this with places like the YMCA).

This idea of third spaces made me realize that I needed them. After learning the term, I’ve been consciously seeking third spaces out. For instance, today my brother and I are going to a rock climbing gym, for the exercise, sure, but also to get a little of the serendipity and magic of community.

There is a loneliness epidemic happening in the USA. Let’s create more third spaces for people to gather!

—

Here are some other names for things that have helped me see the world more clearly:

Values / Alignment – Underneath our language, our thoughts, our actions, and our emotions are our values. Such a simple concept, but seeing life through the lens of values has been quite useful. A related term is alignment — how closely am I living by my values? (Credit to Mark Manson)

Mimetic desire – People naturally want what other people want. This isn’t always bad, but can lead to pursuing things not aligned with my values. For example, in college, there was a period when everyone seemed to be finding a job in investment banking or business consulting. And guess what? I applied for jobs in consulting, even though I had no inherent interest in this field. Thankfully, I wasn’t successful! (Credit to Rene Girard)

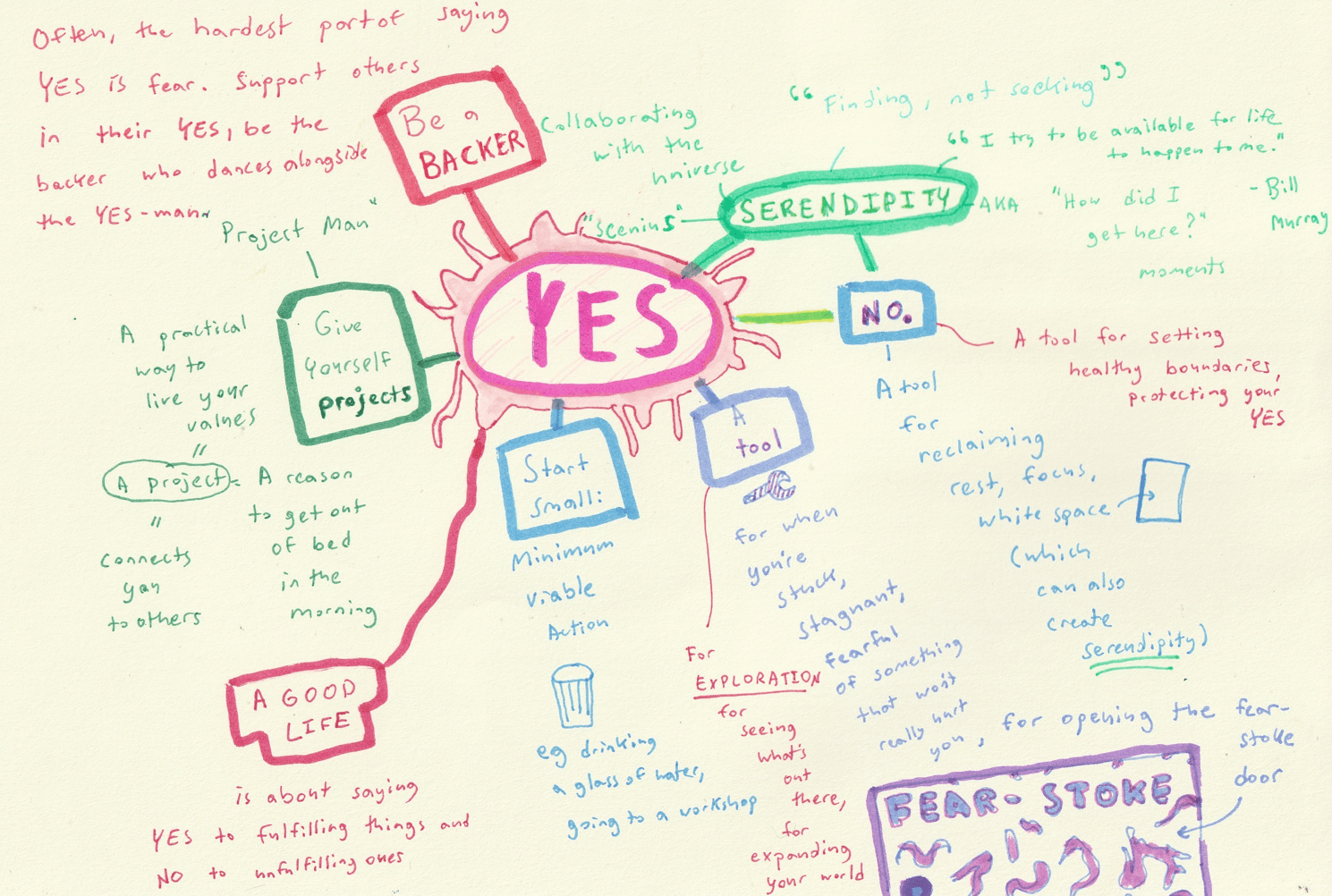

Scenius – A portmanteau of scene and genius. We don’t have to go it alone, self-disciplining ourselves into excellence. Excellence can be simply the product of community support. This idea is ancient. In Buddhism, one of the jewels is the sangha, the community of practitioners. It’s a lot easier to meditate in a group rather than alone. (Credit to Brian Eno)

Flow state – A state of state of presence and aliveness that comes from being challenged a little, but not too much. Since learning about flow-states, I’ve tried to seek them out. Activities that produce flow states for me: rock climbing, writing, dancing. (Credit to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi)

Spiritual expansiveness – To me, this means a state of consciousness that is able to appreciate the primary miraculousness of existence: that I have a body, that I am small in space and time, that I’m interconnected with so many things. Since coming upon the term, I’ve been looking for ways to stoke this sense in me, on the daily. (Credit to Ethan Maurice)

Illuminators and diminishers – Illuminators are people who are curious in conversation, who ask questions, who illuminate the other. Diminishers diminish the other person by oversharing their opinions, not listening, talking excessively about themselves. Now that I know these terms, I can more consciously strive to be an illuminator. A good tool for this is asking questions that start with how/what, and to show up to conversations with vulnerability, without an agenda, and striving for empathy, curiosity, and wonder. Credit to David Brooks and Joe Hudson.

Intercultural relationship — Coming upon this term helped me to see that I was in one, which comes with its own possible challenges as well as fruits. Also, all relationships are to some extent intercultural, because people come from different family cultures. Credit to Ethan Casey, Chat GPT, Rabbi S.

Saying no / JOMO / BOMO — Realizing the importance of these related ideas is something that continues to be hard for me, that I continue to practice. JOMO = Joy of Missing Out. BOMO = Better off missing out.

Existential depression and anxiety — Sadness and anxiety relating to facts that are baked into the human condition no matter what culture or country you live in. Facts like death, cosmic insignificance, and choice that all humans grapple with. I write more about this here. Credit to Irvin Yalom.

Implicit vs explicit culture — At a meditation gathering, I lay down on the ground and the woman next to me said, “Do you have back pain?” “No,” I said, confused about why she was asking me this. There was an awkward pause as I connected the dots: Oh, what she’s really saying is don’t lay down in the meditation hall! There are certain cultures (Japan comes to mind) where things are understood implicitly, through context, without explicit verbalization. There are other cultures (NYC comes to mind) where people are very direct with their words. The reasons are myriad, but this lens helps me to realize that not everyone needs to communicate in the same way. When implicit cultures work well, they are probably more efficient, because things are understood without overt explanation. (Credit: Skyler and Rabbi S)

Progressive Desensitization / the fear box — Fear keeps us in a box. The way out of fear is progressively desensitizing yourself to the thing you fear. This is captured in the quote: “The only way out is through.” Examples in my own life include nudity and nonclownformity. In the show White Lotus, there is a wealthy character named Victoria Ratliff, who has a great monologue when she is explaining to her husband why she doesn’t want her daughter Piper to join a monastery. “We need to teach her to fear poverty so she makes good decisions.” Her husband says, “But what if we lose everything.” “We won’t lose everything,” Victory says. “And if we did, I don’t think I’d want to live. At this age, I don’t have it in me to live an uncomfortable life. I don’t think I ever did” (click here to watch the clip). Victoria lives in a box of fear of poverty, which probably limits her experience of the world. Ironically, if Victoria wanted to get out of her fear box, exposure to the fear (for example, by joining her daughter in the monastery) would be the exact way for her to get out of the fear box. Credit: Corey Muscara, Mark Manson, Peter Lin.

Inner critic / Spirit of Unconditional Love (SOUL) — When I first heard the term “inner critic” I immediately understood with it. “Oh, that harsh inner voice has a name!” I thought. Lately, I’ve been doing a practice where I journal to myself from the Spirit of Unconditional Love (SOUL). This is a way to practice strengthening the muscle of self-compassion. The Grateful Dead sing: “‘Aint got time to call my SOUL a critic, no.” Credit to Sharon Salzberg and Liz Gilbert.

Sophistry — The sophists were a group of people in ancient Greece who taught effective rhetoric, but they didn’t care about the truth. What they cared about was winning. Socrates railed against the Sophists. “The truth matters!” Socrates said. Socrates chose to drink poison hemlock rather take back things he said. He valued the truth more than his own life. These days, there are plenty of politicians twisting facts, fabricating them, and hiding them. Thousands of years after the Sophists and Socrates, here we are. Knowing about Sophistry helps me see what’s going on now more clearly. As Pink Floyd sing: “Haven’t you heard, it’s a battle of words.” Credit: The Good Life Method

High-control group — The term “cult” gets thrown around a lot these days, but I think the term “high control group” is better, because it gets to the heart of what destructive cults are about: control (through fear, shame, and any number of other influence techniques). This term is an internal litmus test I can apply to any group I’m a part of. Credit: The Vow (show)

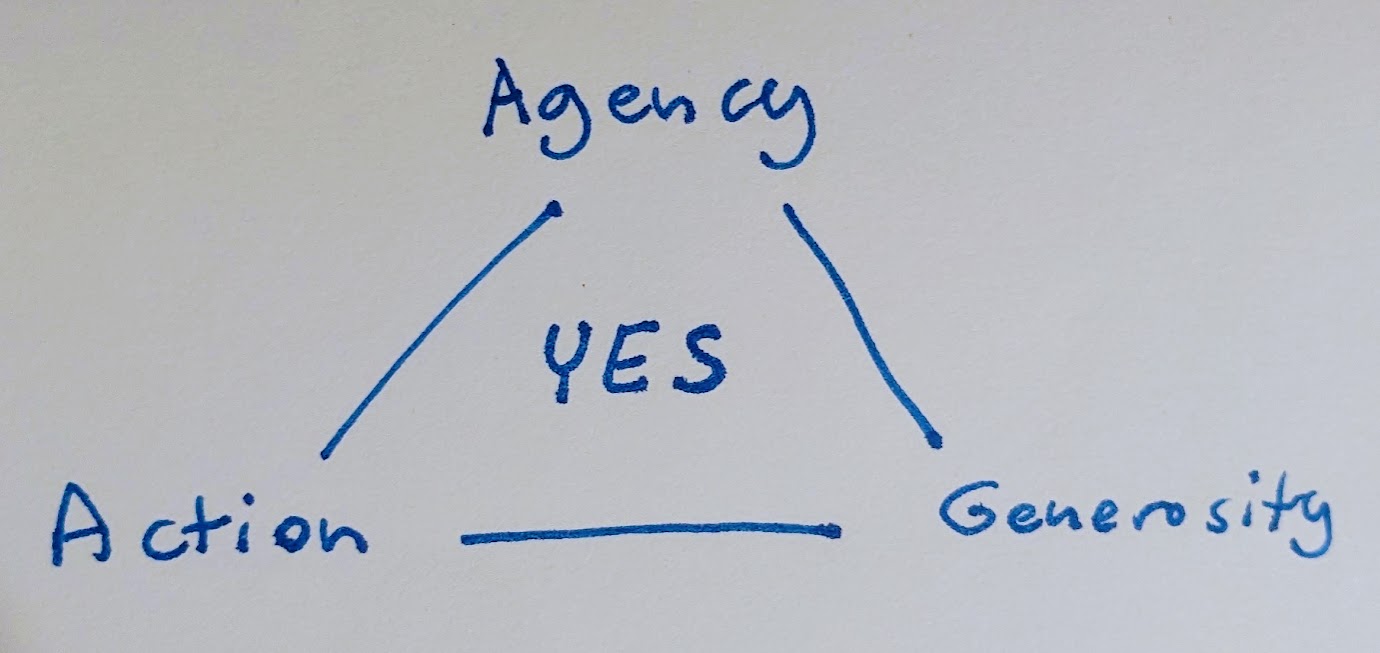

Old Happy / New Happy — Old happy = 3 beliefs: “I’m not enough”, “I’ll be happy when I achieve X” and “I have to do it alone.” New happy = develop your gifts and use them to help others. Credit: Stephanie Harrison.

Strodes –– The word “strode” is a pejorative term to describe something between a street (designed for walkability) and a road (designed for high-speed travel). Strodes abound in the suburbs all around the US, and they kind of suck. They inhibit walkability, serendipity, community, and speed of travel. Once I saw them, I see them everywhere!

Play personalities — Competitor, Creator/artist, Director, Joker, Kinesthete, Storyteller, Collector. It’s fun to see these behaviors as forms of play.

Chromophobia — In the northeast, bright colors are distinctly countercultural. I realized this after coming back from my clown trip to Mexico when I realized that my whole waredrobe was a collection of blacks, greys and browns. The past few years, I’ve been incorporating more color into my wardrobe, swimming against the cultural current of chromophobia.

Reality tunnel — When in one type of media consumption, I can get into a reality tunnel where I think that perspective is all-true and the only perspective. “It’s good to not attach to any one story too tightly.”

My mental lenses

It took me a long time and most of the world to learn what I know about love and fate and the choices we make, but the heart of it came to me in an instant, while I was chained to a wall and being tortured. I realised, somehow, through the screaming of my mind, that even in that shackled, bloody helplessness, I was still free: free to hate the men who were torturing me, or to forgive them. It doesn’t sound like much, I know. But in the flinch and bite of the chain, when it’s all you’ve got, that freedom is a universe of possibility. And the choice you make between hating and forgiving, can become the story of your life. — Gregory David Roberts, Shantaram

Even digestive sensations have their own replica in the brain, thus enabling strange illnesses like that of a woman who, after a stroke, felt the food she swallowed travel down her throat and descend into a nonexistent cavity in her left arm, a disquieting disruption in visceral virtuality. The limbic brain, too, models the world making our emotional realities a set of neurally generated phantoms loose in the mind. Reality is thus more personal than daily life suggests. Nobody inhabits the same emotional realm. Many people live in a world so singular that what they see when they open their eyes in the morning may be unfathomable to the rest of humanity. When one woman looks at an attractive man, she sees someone who wants to possess her and stifle her creativity. Another sees a lonely soul who needs mothering and is crying out for her to do it. A third sees a playboy who must be seduced away from his desirable and unworthy mistress. Every one of them knows what she sees and never doubts the identity of the man in front of her faithful retinas, her fanciful brain. Because people trust their senses, each believes in her own virtuality with a sectarian’s furvor. It’s the rare person who glimpses the expanse of his own subjectivity, who knows that everything before his mind’s eye is the Hindu’s Maya: an elaborate dream… — A General Theory of Love

If I gave myself the task of counting red cars today, I’d see a lot more red cars than I would otherwise. This silly example points to a deep truth: we always have the power to choose which aspect of reality to focus on.

“Mental lenses” like physical lenses, are tools. Even if we are too sick to leave our bed, even if we are thrown into prison, we still have the power to choose how we see reality.

Here are some mental lenses I’m playing with:

- Learning lens. Approach this problem from a space of curiosity. Realize that I’m not a static being, I can change and grow. Ask: what can I learn from this?

- Overlap lens. Ask: what do I have in common with this person?

- Empathy lens. Ask: what is this person feeling and in what ways does that make sense?

- Grounded optimism lens. In an ambiguous situation, which interpretation brings hope and opportunity? For example, our cat Sticky Rice died and we never found out the cause. I can choose to believe he was poisoned by neighbors, or that it was some kind of accident or health problem. The first interpretation erodes my faith in humanity, so I choose to let it go.

- Long lens. Ask: Will this matter in 10 years?

- Helping lens. Ask: Who did I help today? Who helped me? Who is helping others? Credit: New Happy by Stephanie Harrison.

- Universality of suffering and impermanence lens. See that people are affected by similar flavors of suffering: accidents, disease, old age, death. Nothing is permanent.

- Appreciation lens. When looking in the mirror, say to myself: I accept my body as it is and I appreciate what it does for me. When working, say to myself: I get to have a job where I can help people. When eating, bring to mind all that was needed to bring me this food.

- Responsibility lens. Ask: How did I contribute to the present situation? What can I do to take care of my side of the street?

- Self-compassion lens. Realize that, just like all humans, I’m an imperfect being who makes mistakes, has limited time, wisdom, and energy. Many of us are hard on ourselves for our mistakes. We all make mistakes.

- Miracle lens. Every person is a miracle. A being that can see, hear, think, feel, experience. A unique and precious jewel.

Credit to Alex and Ethan for stimulating my thinking about lenses, and to Alex for the red car example.

Worldview, purpose, community, rituals

Yesterday, I finished reading the book Strange Rites which makes the case that there are lots of new secular religions cropping up in America.

Among them:

- Fan fiction

- Followers of Jordan Peterson

- Social justice activists

- Techno-utopians

- Men’s rights activists

- Modern witches

- Alternative sexual communities

- Wellness culture

A religion, according to the author, provides its members with:

- a worldview

- a purpose for their life within that worldview

- a community

- rituals

The four categories above could equally apply to other groups not covered in this book, like environmentalists, or political tribes. The author describes how increasingly, Americans are “remixing” religion. I know that I am.

“There is no such thing as an atheist,” David Foster Wallace famously said. Through the lens of this book, I take this quote to mean that humans have psychological needs for:

- a worldview that explains things, gives a sense of meaning to an otherwise chaotic universe

- a purpose which gives one a direction for the future, guidance about what to do with one’s life

- a community to fulfill the human need for belonging

- rituals to help foster states of collective joy (“collective effervescence” in the language of sociologist Durkheim), help structure time and mark life transitions

I grew up partaking in Orthodox Jewish communities, of the Chabad flavor. There was a clear worldview within this community: the world was created by G-d, and the Jewish people had a covenant with G-d. There was a clear purpose for life: to follow the 613 commandments (mitzvot) so that one day, the Messiah would come. There was a strong community and rituals.

There was “collective effervescence.” The first time I got drunk was during the festival of Purim at age ten. I drank an entire bottle of 5% Manishevitz sweet wine, while spin-dancing arm-in-arm with rabbis to raucous Klezmer music. It was so much fun!

I fondly remember warm Shabbat dinners during college. Every friday, we sat elbow-to-elbow in a crowded attic, eating delicious food, conversing, and giving toasts. Occasionally, we’d interrupt the conversation to sing a Shabbat song while pounding our fists on the table. These weekly dinners gave me a sense of community during an otherwise lonely time.

There’s a lot of good in traditional religions. I wonder whether the new, remixed and secular religions above will be up to the challenge of meeting our human needs.

P.S. Thanks to Ethan for lending me this book, and being my co-traveler on the pathless inter-spiritual path!

My metaphors

In the book Metaphors We Live By, the author George Lakoff makes the case that humans best understand abstract ideas through physical metaphors.

Here is a running list of metaphors that are useful to me:

- Life is a river. We find ourselves in the present, unable to change the past, able to chart our course to different futures. “You have a right to your actions, but never your action’s fruits.” — The Bhaghavad Gita

- Time is a rock jar. There are unlimited rocks we can put into the limited jar of our lives.

- Activism is a ball pit. Any activist cause, for example, disability rights or environmental regeneration, has many individual projects — balls — that can be helpful to the overarching cause. We can be part of the solution by helping a ball or two or three come into being. We don’t have the power to individually “fix” the entire issue. Credit: New Happy by Stephanie Harrison.

- Love is opening the blinds. Visualize a dark night, and a house illuminated on the inside with all the lights on. Now visualize the blinds opening, letting that light out of the window into the world. This simple visualization helps me get into the embodied feeling of love. A mantra to say while visualizing this: may you be happy, may you have ease, may you feel alive. Credit: New Happy.

- The mind is a garden. The plants we water, be they weeds or seeds, are the ones that will grow. Credit: Thich Naht Hanh.

- Indra’s net. This ancient symbol is saying that within each of us is a reflection of the whole universe. Credit: Sharon Saltzberg’s Real life.

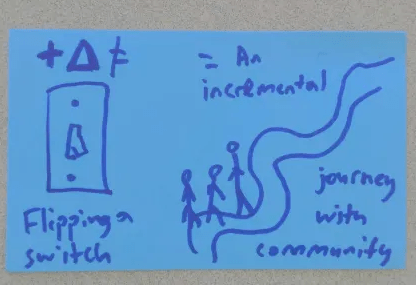

- Positive change is a path, not a lightswitch.

- People are cracked teacups.

- A relationship is a venn diagram. There is the overlap, and the relationship you have with yourself.

- A relationship is a house you co-build. Credit: John Gotteman and Stephanie Harrison.

- A romantic partner is a co-artist on life’s tapestry.

- Values (e.g. friendship, health, learning, love, spirituality) are infinite games, the goal is to keep playing, not to “win” a specific outcome.

- Heaven and hell are places we visit and create in the present moment, in this here life, not in the future.

- The prairie fire burns everything down, but activates the seeds and nourishes the earth for new growth.

Same wine, new bottles

I recently have been learning about the TESCREAL bundle of philosophies, having, myself, partaken in at least 3 of them: transhumanism (through the anti-aging scene of Aubrey DeGrey), rationalism, and effective altruism.

Over dinner last night a friend remarked: “A vision for a future with eternal life? Sounds like Catholicism in medieval Europe…”

Death is a painful thing for an ego to accept. It’s natural to want to deny it. If you’re too rational to believe in heaven or reincarnation, then perhaps a materialist, science-based utopian afterlife is your flavor of wine…

Positive change is an incremental journey, not a lightswitch

The metaphors we live by are significant, consequential.

For a long time, I’ve subconsciously subscribed to the “lightswitch” metaphor of positive change. In this metaphor, I can change my life to a fulfilled, happy state through X.

X can be:

- A book

- A course

- A therapy

- A practice

- A retreat

- A substance

- A philosophy

Nowadays, I’m realizing that there’s a dopamine hit from the early stages of all the X’s above. It’s dopaminergic to believe that THIS THING will solve all my problems, flip the lightswitch of my life.

My pattern would go like this: I would get the dopamine hit from the early stages of X, then lose momentum, and find a new dopaminergic X to imbibe.

The problem wasn’t even necessarily the individual things I got involved in. The problem was my metaphor.

Nowadays, I have a new metaphor: that of an incremental journey. You don’t do a long trail instantly. You have to keep showing up every day, logging in the miles.

And while stretches of solitude have value, overall the journey is better if you hike alongside friends. We don’t have to do the whole hike alone.

Credit to Megan Cowan for calling out my “lightswitch” view years ago, and Em for the “incrementalist” language.

You don’t need to be a poet to be interesting

I think one of the nice things about animals is that they’re unapologetically themselves. When I was growing up, my mom sometimes told me this quote from a Russian poet: “I’m a poet, and because of this, I am interesting.”

Today marked the last day of a book club discussing this book called “New Happy.” This book makes the case that we believe 3 lies that keep us from happiness:

- I’m broken

- I’ll be happy when…

- We need to do it alone

“I’m a poet, and because of this, I am interesting” is the line of thinking that says: to be worthy, you must be accomplished.

Well, a dog or cat doesn’t need to be a poet. The kitten sitting in front of my keyboard right now purring and wearing a cone is content being a purring furball. She’s not telling herself that she’ll only be interesting after she gets her MFA and first collection of poems published.

I had this moment of realization this morning: what if I stopped believing that I need to become something magical and accomplished in the future to be happy. What if I was enough right here and now, just as I am?

My body relaxed.

I like to write poems, but I don’t need to be “a poet.” I like science, but I don’t need to be “a scientist.” I can be a poet or scientist, but kind of as a byproduct of pursuing what I like and what the world needs. Not as a way to “be interesting.” I’m interesting just as I am.

I can let the soft animal of my body be the soft animal that it is. No need to contort myself into some mythic future X. Happiness is right here and now.

My parables

Parables are stories that contain within them a philosophy of life, a worldview. Here are some that resonate with me:

The Buddhist parable of the mustard seed — Life, for everyone, is impermanent and death is universal. Nobody gets their life “together” permanently. See also the poem Ozymandias and the philosophy of Emerson on impermanence.

The parable of the Chinese farmer — With a longer time horizon, the things that are painful today can lead to fruits tomorrow, and vice versa. An example from my life: when my bosses in internal medicine residency said I wasn’t a good fit for the field, it was painful, but it led to me finding a better career fit eventually. And this painful experience helped me be able to better empathize with people in similar positions (and help by way of sharing my story and undoing some shame).

Walden pond — Solitude helps us discover what we really think. My Waldens have been: a hobbit house I rented off Airbnb, six weeks on the island of Kauai, traveling, writing, long runs and swims.

Sartre’s student — The dilemma of Sartre’s student is the dilemma we all face in life: what to do? which values to choose? External “right answers” to many of life’s dilemmas don’t exist (not in utilitarianism, Kantianism, virtue ethics, or religion, though these can provide ideas). We must choose for ourselves.

Camus’ plague — Life is absurd, the universe giveth and taketh away, we have to choose how we live despite this. Do we despair and think of ourselves as a victim? Or do we live with decency and generosity?

The overview effect — When astronauts go to space, some are struck by wonder and awe at the oneness of planet earth and feel a sense of rage at things like war and environmental destruction. From the vantage point of space, we can see the insanity of identification with small differences (as satirized by Dr. Seuss in The Butter Battle Book). Yes, it’s true that the human psych tends to form in-groups. Yet rather than identify as a certain narrow part of our identity, we can CHOOSE to identify as living beings on a planet. Our tribe, then, is all of life. When I think in this way, I feel an expansive feeling in my chest.

The parable of the empty teacup — keeping beginner’s mind is keeping your teacup empty. When listening, practice not thinking what you’ll say, but taking in what’s being said.

The value of depth

I was talking to a friend yesterday who remarked that if she only had 15 years left to live, she’d choose depth over expansion. She’d choose spending time with the people she loved over meeting new people.

This made me think of Spotify, and how the app actually makes my experience of listening to music worse. Yes, I can listen to any music at any time. But this increased ability to expand and explore actually makes it harder for me to really get into any one artist.

When I was in college, I traveled to a remote village in Ghana for several weeks. There was no internet. All I had in the way of entertainment was what I brought with me: a laptop computer and some books. My laptop had only one album on it: We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank by Modest Mouse. I hated this album the first few times I listened to it. But because it was my only choice, I kept listening, on repeat, and eventually, I grew to like, and then to love, this album. I listened to it dozens of times.

In this era of Spotify, there would be no way I’d ever have this experience of struggling through, and then growing to love, an album. The writer Mark Manson said that when one thing becomes abundant, another thing becomes scarce. So many things are becoming abundant these days. It’s easy to meet new people: just join a group. It’s easy to listen to new music on Spotify. It’s easy to find information online.

What’s becoming scarce is depth.

To see the beauty of another person sometimes requires knowing them for years. Our cat died recently, and my wife is grieving. In witnessing her grief, I’m struck by the beauty of her love for our cat Sticky Rice. Yet I wouldn’t have seen this if we’d only known each other for a short period of time.

To see the beauty of a career sometimes requires being in it for decades. I recently reflected on where I am with my career. Zooming out and taking stock, I was able to see the meaning in my past struggles, how those struggles have led me to where I am now. And I was able to better appreciate what I find most satisfying about my current job: the ability to get to know people.

I’m realizing that meaning is proportional to struggle. I’m writing these words with our 90 lb dog Mango warming my feet on the couch. Mango is a 50% good boy now, but there was a time when he was only a 1% good boy. Getting him to this point took a whole lot of training and struggle, and receiving help from a trainer.

Another Mark Manson quote is “Don’t hope for a life without problems.” The problems, the struggles, the periods of feeling lost are what give a sense of meaning when we finally make it out of the woods. Deciding when to quit and when to commit is a subtle art. Yet, in this era when it’s getting easier and easier to pick up a new song, a new book, a new friend, I keep needing to remind myself of the value of depth: that meaning that comes with overcoming struggle, that it’s good to keep at things.

No shortcut to knowing what you like

The only way to know what you like is through experience. After over a decade in medicine, I now know that what I like about it is:

- Getting to know my patients as people (this is my #1 favorite thing)

- Solving puzzles

- Learning

- Helping

- Teaching

I don’t like:

- Publishing papers

- Getting interrupted / woken up

- Being responsible for a very wide range of problems

- Following protocols meticulously

When I was in medical school, I read a few books adjacent to medicine. One was called “My Own Country” by an HIV doctor, who worked in the rural American South. Reading this book, I got the idea in my head that being a general practitioner was “real medicine.”

Yet my experience in internal medicine was not enjoyable. I found being responsible for a wide range of problems, and medical knowledge, to be overwhelming. I didn’t like — and wasn’t good at — being the “manager” of someone’s entire body. After I changed fields from medicine to neurology, I found it far less stressful and more rewarding to be responsible for a single area than the whole enchilada.

While in neurology, I found, after a few years, that I didn’t enjoy inpatient work as much as I thought I would. Though I found the diseases intellectually interesting, the workflow of constantly being interrupted didn’t suit me. So I changed to a more outpatient-focused position where interruptions are minimal.

In addition, in the outpatient world I found that I had more time to get to know my patients as people. I find that when I can glimpse into who people are outside of their diagnosis, my work becomes more meaningful. I did not know, going into medicine, that this would be what I like most about the work. I entered medicine for the medicine. I’m staying because I like people.

Over a decade ago, I read the books, “Surely you’re Joking, Mr. Feynman” and “For the Love of Enzymes” and “Advice for a Young Investigator,” which gave me the idea that it would be awesome to be a scientist. To make discoveries. To follow my curiosity.

My actual experience in science was different from the picture I got in these books. Over many years, I worked in four different labs. I studied the cell biology of aging, tissue engineering, biochemistry, and neuroscience. I was super-interested in each of these topics. Yet, the day-to-day, boots on the ground experience of working in these fields was not something I enjoyed or was good at.

When I worked in research, I found that a tremendous amount of patience was required: organized notebooks, following protocols meticulously. I realized that my nature is to be an intuitive cook — a little of this and little of that — not a fastidious baker.

OK, I thought. Maybe I don’t have to be in a wet lab. Yet, when I took on the project of writing a review paper, on a topic I enjoyed (meditation), the process was still excruciating. It seemed that wherever I tried to enter the world of research, I couldn’t find flow.

The writer Mark Manson asks the following question: what’s your favorite flavor of shit sandwich? By this, he aims to underscore that every path involves failure on the way to gaining competence. For me, the path of studying was somewhat enjoyable. I’m naturally a pretty good student and test taker.

Yet the practice of science or medicine is not really about studying. Being a scientist is about working in the lab and writing papers. Being a doctor is about seeing patients. I realized, only through experience, that I enjoyed the latter but not the former.

Manson asks another fecal-themed question: what makes you forget to eat and poop? By this, he means: where do you find flow? Where do you enjoy the process?

I don’t think it’s possible to answer this question without actual experience. I can read books about something, I can talk to people who do it, I can even shadow people, but until I’m actually doing something myself, for a decent chunk of time, I won’t know if it’s my thing.

I like the process of rock climbing. If you put me in a rock climbing gym, I can hang there for hours and get into a flow state. The workout happens naturally. If you put me in a standard gym, I can force myself to lift weights, but it’ll be a slog. This knowledge about what kind of gym I like came only through trial end error. I don’t mind falling off rock climbing walls. But I don’t like the repetitiveness of a standard gym. So my favorite flavor of gym shit sandwich is rock climbing. Rock climbing makes me forget to eat and poop.

There’s this common advice that goes: do what you like. Yet, I think that the doing is the second part. The first part is knowing what you like. And this knowing can take decades to arrive at, and a whole lot of tweaking and self-reflection.

Knowing that I like “medicine” was just the first approximation. It took a whole lot of tweaking to find a practice setting that has enough things that fulfill me where it’s sustainable. My current job isn’t perfect, but reminding myself the above lists helps me to realize that it’s pretty good.

I saw a patient yesterday whom I feel like I’m really getting to know as a person. I’m working on a difficult diagnosis in his case. I don’t think I’ll be able to help “cure” him — but nonetheless, the process of working towards some kind of answer, and getting to know him in the process, is meaningful.

In my medical school essay, I wrote about my experience working with an eye surgeon in Ghana who helped restore sight to thousands through cataract surgeries. This was the model of medicine I had in my mind: doing great good for people through treatments.

I’m a different kind of doctor, I’m realizing, a slower kind. I like to know people’s stories. I’ve expanded my definition of helping. Yesterday, I saw a patient with headaches. I prescribed her a pill for migraines, but I spent much of the visit talking about the stress in her life and who she is as a person. We did a meditation together and she told me about her job, where she’s from, her family. I found this process of getting to know her the most meaningful part of the visit.

Let’s say that the pill works magic and cures her headaches. I’d be happy about the result, but my main meaning would come from the knowledge of what this improvement means for her in the context of her life.

It’s taken me decades to “know what I like.” Lots of trial-and-error and reflection. “Do what you like” is like an advanced graduate-level program. “Know what you like” is the first step and has taken me a whole lot of time.

Practice holding yourself

I listened to a podcast yesterday where two former addicts were discussing how self-love was so hard.

This got me thinking, this morning, about love. I’ve mused about love extensively in the past. This morning, I had a bit of clarity about what love means to me. Much like spirituality, it’s a tough word to define. Like spirituality, I’ve done a bunch of reading about it, and I’ve sought it out in the world. I’ve looked for love in romantic relationships, in friendships, and in prestige, in “likes.”

While I got “high” from these experiences, none of them ultimately proved to be a durable source of love.

In the past week, though, I did three practices which helped me access self-love:

- Body scan — I went up and down my body, focusing on areas of tension. Wherever there was tension, I gave this area the warm light of my attention, breathed in, and breathed out just a little bit of that tension.

- Letters from love — I wrote several letters to myself, inspired by the prompt “Dear love, what would you have me know today?” Credit to Liz Gilbert.

- Guidework — I did a guided meditation where I went underground and met up with my buddy Thich Nhat Hanh who gave me some unconditional warmth and acceptance. Credit to Megan and Chris.

It strikes me that these different words we use — words like understanding, acceptance, belonging, being seen, and love — all point to an energy, which, as close as I can put it in words, amounts to the energy of being held.

So is self-love hard?

Well, we have parts of ourselves that aren’t very loving. When lost in these parts, we can search for love in the external world. I remember reading once that using heroin was like “being hugged by Jesus.” I’ve never been a heroin addict, but I’ve done essentially the same thing a heroin addict does: looking for love outside myself.

I now know that there are ways I can access loving energy within me. Yes, it’s nice to get love from people in my life too. But if I can’t provide love for myself, then I’m a “hungry ghost,” always searching for a feel good boost externally.

And also, the muscle that loves myself is the same as the one that loves others. Self-love isn’t selfish. Practicing it is actually the best thing I can do to really love others.

Kimya Dawson sings, “You can be sober, and not recover.” Even if one doesn’t use substances, one can be a hungry ghost, filling the need for love with X.

X can be many things.

A few of mine, over the years: shopping, romance, workaholism, new year’s resolutions.

In the podcast, one of the former addicts talks about “getting to the root cause of addiction.” I think the root cause of addiction is always the same: it’s the inability to hold oneself. To escape from an unpleasant inner empty feeling, the addict chases highs. It’s new years resolution time, and I’m reflecting now that for years, my drug of choice has been progress.

There’s nothing wrong with progress. Nothing wrong with exercise goals or dating or decluttering the house. But what is not healthy is using these things to escape a sense of inner emptiness.

Practice holding yourself, Dan. You can still go on the run this morning. But also, practice holding yourself.

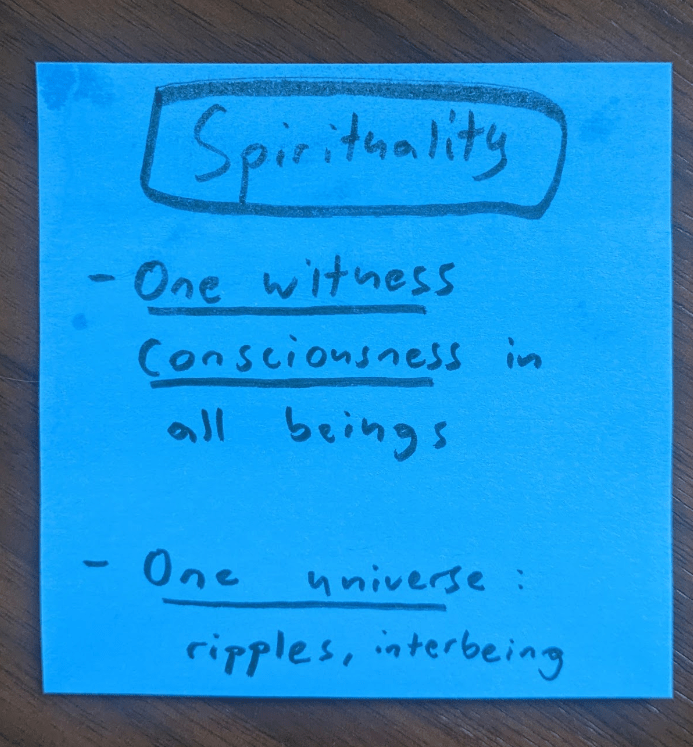

Spirituality = oneness

I’ve mused about my definition of spirituality a bunch on this blog. For example, here’s an early musing, from over a decade ago.

Fast forward to today, and I think I’ve come to “the simplicity on the other side of complexity.” Here’s my current definition of spirituality, small enough to put on a post-it:

For me, spirituality is a way of seeing that emphasizes oneness. This comes in two flavors:

One witness consciousness in all beings

A common metaphor for consciousness is the blue sky and clouds:

The blue sky is the observer or witness consciousness. Clouds are thoughts/feelings.

The observer consciousness — the blue sky — is the same in all sentient beings.

Two quotes:

You and me, that is the awful lie. It’s I and I. — Conor Oberst, from his song One for me, one for you

I honor the place within you where, if you are in that place in you, and I am in that place in me, there is only one of us. — Ram Dass

The egg is a sweet animated story that makes a similar point to the quotes above.

A penpal of mine gave this pointer: if you look at someone’s pupils, the witness consciousness on both sides of the gaze is one and the same. The two people don’t have the same mind or the same thoughts and feelings. But they do have the same observer consciousness. The same blue sky.

One universe

I have to give credit to Thich Naht Hanh for really bringing this teaching to the forefront of my attention. When we drink tea, there’s a cloud in the tea. Before we we born, we lived inside our parents, and before that, in our grandparents. After we die, the ripples we left in the world will continue. There is no birth, no death, and no independent self.

There is no such thing as a tree independent of the earth, the clouds, the air, the sun. The entire universe is a system that inter-is, changes and morphs through time. Seeing in this way promotes a felt sense of connection.

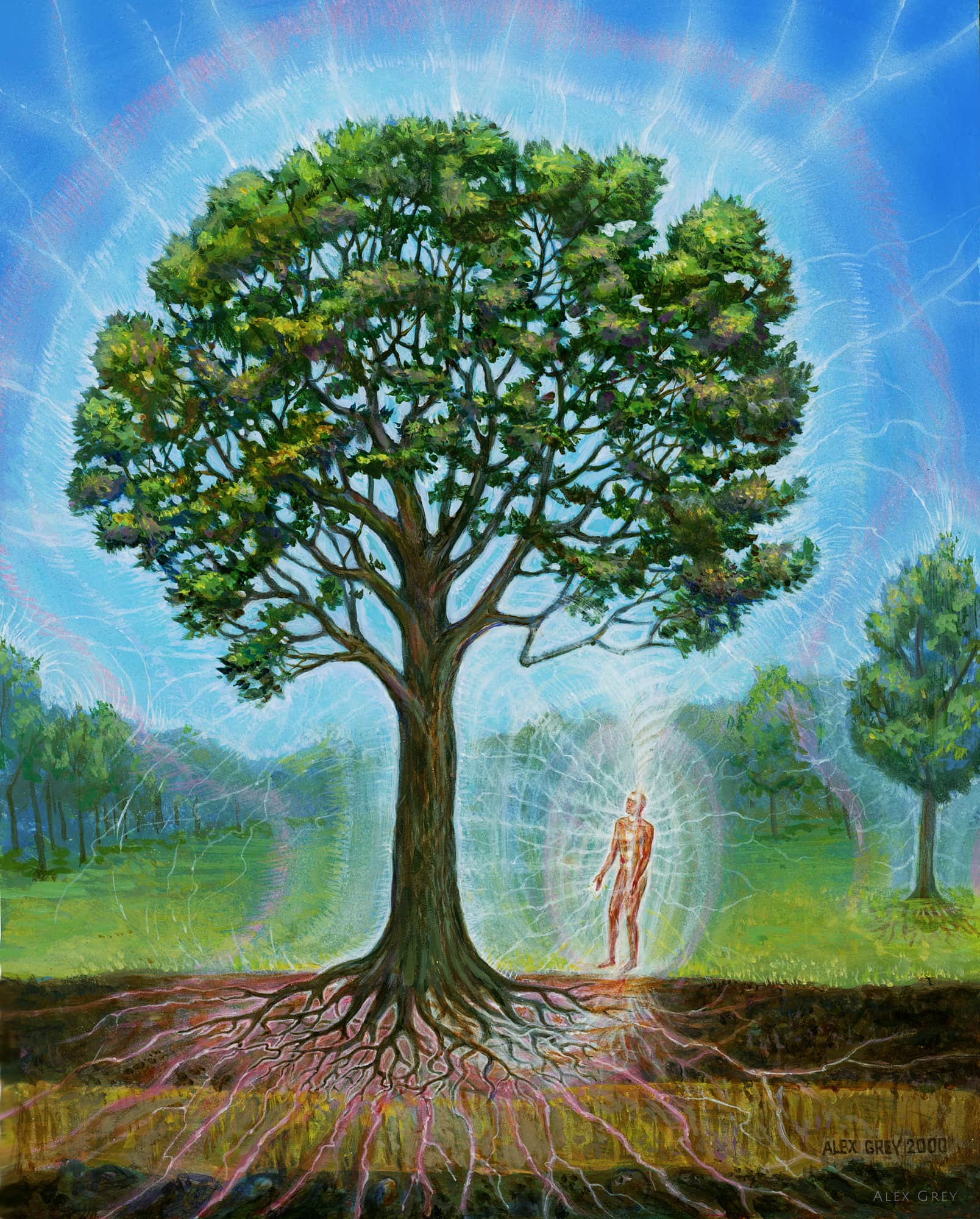

The art of Alex Grey underscores both of these forms of oneness, for me:

I’m only now realizing that there’s a subtle latticework permeating each artwork above. Could this be a symbol of oneness that connects us all?

For me, spirituality is not about belief in a deity or anything supernatural (like reincarnation). It’s about putting down the illusion of separateness, and waking up to our oneness with each other and the universe.

2025: Annual Post-It Note

Here’s my minimal and intuitive “annual post-it note” — the things I want to focus on in 2025:

Theme for the year: Make my decisions right

Intentions for 2025:

— Practice noticing

— Use my toolbox

— Open up to newness, do something

— Move all the time, not just while “exercising”

— Garden and mentor

My toolbox

Everything is a tool. — Mark Manson

Or: every practice, lens, philosophy is a tool in the toolbox of life.

This perspective has been helpful for me because it keeps me from falling into the thinking that that I need to find the “one thing” will make all my problems go away. This is the sort of thinking that gets people into following culty cult leaders.

I can pick up tools, play with them, and put them down as I need to. I’ve created this running list to remind myself that I have lots of tools to draw from:

- body scans

- letters from love

- tea ceremonies

- juggling

- clowning

- medicine learning

- seeing patients

- cooking delicious food

- walking

- running

- swimming

- climbing

- slacklining

- talking to friends

- community (WUH, men’s group)

- shabbat

- volunteering

- doodling

- living life as art

- dance and freeform body movement

- sunsets

- hugging trees

- noticing colors

- psychotherapy

- journalling

- blogging

- spirituality

It’s a simple and generous rule of life that whatever you practice, you will improve at. — Elizabeth Gilbert

Be with the eggs

In response to my recent post about death, a friend said, “Our ego’s hope for a grandiose legacy isn’t what we’re here to do. It’s to serve our purpose in this continual moving on.”

This reminded me of the word “autotelic” which means “for its own sake.”

My favorite joke:

Two old jewish men are chatting in the shtetl. One says to the other, “Tell me about your business.”

“I buy eggs for a rubble, boil them, and sell them for a rubble.”

“What’s the point? You don’t make any money.”

“I get to be with the eggs.”

Go for the autotelic! Be with the eggs.

The autotelic is our purpose, in the continual moving on.

Philosophy of pleasure

“What’s wrong with pleasure?” my therapist once asked me.

I think she was reacting to something self-shaming that I’d said. While I don’t think there’s anything morally wrong with pleasure, I do think that pleasure can lead us astray because it can be addicting. On a recent trip to Japan, my wife and I walked through a doorway on a Tokyo street and saw this:

This was a Pachinko parlor, were visitors, mostly men, gambled in a game that’s something of a cross between slot machines and pinball. The pachinko industry in Japan is worth $200 billion — 30 times what Vegas makes in gambling, and double the size of Japan’s export car industry. Crazy!

So, do we become Puritans or Spartans and avoid pleasure entirely?

I don’t think that’s necessary. I think we can upgrade pleasure by adding one of three ingredients (or two or three):

- Memory — we can use pleasure to create a memory, for example going to a fancy dinner to celebrate a birthday

- Community — we can share pleasures with loved ones, for example having a wedding dance party

- Mindfulness — we can consciously savor pleasures, such as mindfully eating a tangerine

So after thinking about it, I would say to my therapist that yes, I do think there is something wrong with pure pleasure, because it can potentially isolate us. It lead us into a state of addiction, of chasing sugar or Pachinko highs. But if we upgrade pleasure with the ingredients above, then it can be a great thing.

Thank you, Arthur C. Brooks, for these insights.

It doesn’t matter who comes to my funeral

I’ve been thinking, of late, about who will show up to my funeral. Maybe it’s because I recently got married, and went through the difficult process of deciding who to invite.

I’ve caught myself thinking, in the back of mind: who are the people who will take the plane to my funeral? As if this were some kind of measure of my life and quality of my relationships.

Yet ultimately, perseverating on such a list – be it for a funeral or wedding – is arbitrary and an example of black-and-white thinking. Just because someone was at my wedding doesn’t mean our relationship is super-meaningful. Just because someone wasn’t at my wedding doesn’t make the relationship worthless. Grey areas abound. Relationships are dynamic things that evolve over many years.

Yesterday, I got a call with sad news that a friend had died. I donated to the fund for her funeral, but I likely won’t likely be booking a flight. I don’t believe that her soul is at peace or not at peace or in purgatory. I believe that she lives in the ripples she left in the world.

I lit a candle for her yesterday, and talked to people about her. She now also lives, a little bit, in these people who have heard about her and have never met her. She lives in the air of my room, which is different now that the ritual candle has been burned for her. She lives in the $25 dollars I donated to a cat rescue fund in her honor. If that organization gets to pair one more cat with owner, thanks in part to that $25, then she’ll live on there, too.

The writer Mark Manson told the story of a transformative moment of his life. When he was a teenager, he spoke to a friend of his at a party. And then that friend, a few minutes later, jumped off a cliff to his death. His friend had miscalculated the depth of the water, and got shattered on rocks. One moment, the friend was having a good time at the party, the next, he was dead. This was the moment that “we’re all gonna die” really registered for Manson, emotionally.

I’m in a similar moment right now. But there’s more to it than that.

I shared my grief with a friend, who told me that his dog of 15 years had died suddenly. The kids in his household, who are young and hadn’t spent much time with the dog, didn’t seem to care.

In a brief span of time, my friend saw the jarring juxtaposition of two things:

- The suddenness of death

- The world moving on

The first thing — “Memento mori” — seems to be becoming mainstream, which I think is healthy. Yet the second point isn’t talked about as much: that world moves on. Sometimes quickly, that very day, as with the kids and the dog. Sometimes it takes a while. But the world does move on.

When I die, a very tiny fraction of this world’s billions will be emotionally affected, and some of those will show up to my funeral. Some will grieve in other ways, perhaps by lighting a candle and swimming in the ocean and looking at the setting sun, as I did yesterday.

Some might write, as I’m doing now.

All will hopefully return to their lives, as they should. As I want them to.

The moments I shared with my friend now seem extra gone, now that the book of her life is shut, and there’s no opportunity for me to pick up the phone and write another page. Yet they are also not gone. They live on in me.

My friend who lost his dog said: “If this is true – that I’m going to die and the world will keep going – then there’s absolutely no reason to live inauthentically, to preserve the version of myself that’s acting out of fear, to burden my future self with regret.”

He told me that his boss wasn’t very empathetic when he called in and said he needed time to grieve. He told his boss, “Look, I’m here to help, but I’m not going to work just because you and I have different ideas about what grief is supposed to look like.”

This small act of standing up to his boss is what it looks like to pursue our values, to live in authenticity.

Whether 400 people come to my funeral or just four, whether I die at 40 or 100, the basic facts are still the same:

My physical body will die. The world will move on.

The ripples I made during the days of my life will remain. They will combine with a myriad of other ripples, and become part of the world of the future.

National values

In our plane coming back from Japan, this video played for all the passengers:

To me, this video emphasized working together towards a common good. The person in the wheelchair was being helped by many. Every person had pride in their work, from the corporate people with their powerpoint decks, to the chef, to the pilot, to the cleaning crew.

At US customs, another video played, which featured visible diversity: an interracial couple, people of many more diverse ethnicities (compared to the above video), and also someone in a wheelchair. This person, however, was not being helped: they sped down a long road in a racing wheelchair, biceps bulging and sweat pouring down their torso, likely training for a competition.

The values emphasized in the US video were: diversity and individual achievement.

In the airport elevator back in the US, I noticed scratches, graffiti. Thinking back to the past week in Japan, I realized that my wife and I had only seen graffiti once, despite spending nearly all our time in cities. The Japanese elevators were immaculate. They even had thoughtful touches such as an “emergency kit” which included a bathroom bucket, food, and even playing cards (in the event that the elevator gets stuck). Below the elevator buttons was a pad to discharge any static electricity on one’s fingers.

These differences between elevators, airport videos and graffiti are fractal-like: in these little fragments of culture we can see the major differences in values between the US and Japan. Every value has a shadow side. The shadow of being very considerate is a stifling of self-expression, a theme that’s come up in my conversations with several Japanese expats. The shadow of individualism and diversity is loneliness and chaos, because people are not on the same page, not looking out for the common good.

Another example: I recently spoke to a German friend about the value of “being rich.” In Germany, being rich is seen as a negative thing: it means you are likely not honest or lazy, achieving a high level of wealth through hoarding resources or inheritance. In Germany, very wealthy people would actually be less likely to be elected because of this national value. This is such a contrast to the US, where billionaires are often lionized on the covers of magazines, in popular songs, and where one was just re-elected president.

Nations have values. Families have values. Individuals have values. These values interact. In his book, How to Know a Person, David Brooks asks the question: “How are you both a cultural inheritor and cultural creator?”

While we are “thrown” into our cultural world, we still have choice. We can embrace our nation’s values, or rebel against them. If we really don’t vibe with our nation’s values, we can even choose to become an expat (this requires a degree of privilege as well as sacrifice).

Traveling to Japan made me come back to the US and see the values here more clearly. Spending time in other people’s homes does the same. I have a friend whose family values frequent big communal dinners with lots of wine. My uncle Buma valued long and serious deep-dive conversations, where he really got to know people. Both of these are different from how my family operates. Neither is “right” nor “wrong.”

The Grateful Dead sing, “sometimes we visit your country and live in your home, Sometimes we ride on your horses, sometimes we walk alone…”

The benefit of travel, be it halfway around the world or to friend’s house for dinner, is that we get to see how other people do things, and when we return, we get a clearer view of ourselves. In the words of Wade Davis, “The world in which you were born is just one model of reality. Other cultures are not failed attempts at being you; they are unique manifestations of the human spirit.”

Little cherishments

The wedding band

Hangs with the keys

In my keyring

I put it there

So I wouldn't lose it

During my swim in the ocean

This little action

Weaving it into the keyring

Weaving it out

Putting it back

On my finger again

Is symbolic

Of the fact:

A big part of life

Is how you show up

A sprig of chillitude

Yesterday I had a new kind of thought

A new kind of feeling

I approached the car and

Realized that my keys

Were back in the locker room

My feet started to run

Nervous system

Going into high gear

I slowed back down

The new thing came over me:

If I lose my keys

If I lose my car

It will be okay

Space will open up

For something new

Kindness for the mean parts

Yesterday, I mailed a gift to my parents by boat.

“It will arrive in 20 days,” said the man at the counter.

Walking out of the post office, I ran into a friend, who was sending multiple boxes by priority mail. I realized then that it would have been cheaper and faster to send my package priority.

“Damn it,” I said to myself. It was too late to go back and change course.

In the car, I listened to an audiobook called Between Two Kingdoms which describes the author’s experience as a 20-something with leukemia. Compared to the author’s life challenges, this package incident was so minor.

Yet here I was: judging myself for imperfect mailing. And judging myself for judging myself.

There are two tri-lettered flavors of psychotherapy that I like: acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and internal family systems therapy (IFS). Both emphasize compassion towards thoughts and feelings that come up. Both emphasize living a values-driven life.

I choose to value self-compassion, learning and love.

I’m not going to be perfect. Mistakes are doorways to learning. Yesterday, I learned about the best way to mail things at the post office: get the priority box, pack the box at home (or come prepared with a sharpie marker and some crumpled papers to use as padding), and mail.

Even though I mailed the things imperfectly, I’m glad I got out the door yesterday and mailed them. Sending gifts is not my usual love language. This was a growth-edge for me.

I visualize the perfectionistic part of me as a guy wearing a black suit and tie. He looks a little like Lex Fridman:

Early on in my life, this guy internalized the idea that in order to be loved, he had to be perfect. So naturally, he is judging me about the package.

Suit-and-tie guy can’t be erased. He has to be embraced. He is wounded, and believes that only by getting it “just so” he’ll be loved. He doesn’t know that he already is.

The solution for suit-and-tie guy’s meanness is compassion, kindness. Mean parts of myself are mean because they are driven by fear. They believe they are serving me. Since I can’t erase them, I want to learn to embrace them. To take a wider and warmer perspective.

I can remind myself that the package incident was an opportunity to learn. My parents will still be happy when it arrives in 20 days. Sending it was aligned with my value of showing love.

Yet the suit-and-tie guy still got activated, despite these facts. He said: You are such an idiot. The package won’t arrive before the holidays. Who knows, it might get lost. And you had to use more packaging to send it the way you did.

I can say to him:

I see you. I know you’re trying to help. Come here, let me give you a hug.

Jack Gilbert died of Alzheimer’s

Jack Gilbert

Would not have

Wasted the experience

Of peeling the clementine

Strands delicate and white breaking

As flesh separates from carapace

He would not have wasted

The sensuality

Of exploding droplets

Citrus fresh

Aerosol fireworks

Did it matter

That at the end

He was in a home?

Not gazing greedily at the Aegean

Or the nipples of a lover

Or savoring a meal of fish

In a year of solitude

As swallows flew

Overhead

I don't know where my last hours will be spent

More reason, then, to embrace the scene

Cat nestled on table's corner

Dog on couch

Greasy hands from lunch

Pen on paper

Birdsong, bells

Wind on skin

Wiggling ferns

And yes

The clementine

Today

Believing in slow healing

A year and a half ago, I fell from the top of a 20-foot bouldering wall onto a foam mat. Immediately, I felt a sharp pain in my left Achilles tendon. I brushed myself off, thinking it wasn’t a big deal.

Over the next few weeks, dull pain continued in my tendon, and over the coming months, it did not get significantly better, despite lots of rest. I eventually saw an orthopedist, who suggested more rest, and wearing a boot. I didn’t wear a boot, but did do more rest.

No enchilada. The pain kept on pain-ing.

Eventually, I started to tell myself the story that I’d always have the pain, for life.

Then, I looked up some exercises and saw another doctor, and a physical therapist. The exercises were so boring! I printed them and put them on my fridge. Still, I did not do them.

Then, I enlisted Ron, a personal trainer, to help hold me accountable. During our workouts, Ron always made it a point to have me do my achilles PT exercises. After a month of doing the super-boring exercises semi-consistently with Ron’s encouragement. I began to see results. Today, after a run, I barely feel my Achilles tendon at all.

I think there’s a larger lesson in this Achilles story: my fixed mindset that I would never get better was keeping me from getting better. It’s like that old saying: “Whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re right.”

Here’s to thinking you can, and then doing the work, with help from backers.

The clown lens on life

It’s been a year and a half since I delved into the world of clowning. My practice is to clown in everyday life: in the grocery store, in airports, on trains, on city streets.

The main thing that I’ve learned through this practice is that a lot of life is how you show up. A clown chooses to show up with specific intentions, not on autopilot.

Prior to clowning, my wardrobe was drab by default. I had unconsciously chameleoned my color scheme because that’s what everyone else was wearing. Now, I realize that drab colors are a choice, and bright colors are also a choice.

The clown lens on life is: all of life is performance. The clown puts on bright clothing and shows up with an eye towards promoting play, joy, humor, and connection. The clown is not merely an agent of chaos, weird for the sake of weird. The clown is a clown because she chooses to value the above things more than conformity.

There’s a story Elizabeth Gilbert tells about how she was on a New York City bus and the driver told everyone that he would be willing to shake their hand and make their day a little bit easier. The faces of the people on the bus instantly relaxed and people took him up on his offer.

This bus driver showed up with an intention to create connection and compassion in his space. It didn’t matter that the weather was bad. It didn’t matter that he was at work. It didn’t matter that he might have been tired or that people were not in a good mood. He showed up in an intentional way.

This is what a clown does. But you don’t have to be a clown, you don’t have to put on bright clothing and a red nose, to show up intentionally. I’ve discussed elsewhere how at the hospital where I used to work, there was a cashier who would play music and have inspirational quotes prominently displayed: every day spreading good vibes to her customers. From a broader perspective, this too can be seen as clowning.

Yet even without non-conformist actions, we can learn from the clown.

Do we see the good in another person and compliment them? Or do we see the flaws and berate them? When we go out to a restaurant, do we see the beautiful mural on the wall? Or do we see the problems with our meal?

I think a BOTH/AND perspective is the truest: we need both the happy and sad clowns in our psyches. We can’t just ignore the fact that we’re tired, or grieving, or just not feeling like connecting. That’s totally okay. Rest and grief are important. Yet it’s also important, I think, to skew positive. Because if we skew positive, we promote positive neural pathways in our minds and we become more positive. It’s an upward spiral.

My most recent clown-outing was taking an Amtrak. I had been with my family for a week and a half, and I was stressed because two family members had fallen ill. I was not feeling much like clowning, but I still put on my outfit. During that train trip, I connected with at least four people very positively, and gave away three “In this together” bumper stickers in my character, The Clown of Interbeing.

The lady above showed me photos of her dog, which she takes to play with neighborhood kids. She shared with me her spiritual practice. If I hadn’t been dressed as a clown, I would have just walked by her. Clowns attract other clowns. There are hidden clowns everywhere!

You might be one too, and just not know it yet.

And also: clowning may not be the tool for you.

I hope that by sharing my clowning journey, I inspire you, a little bit, to find your way of showing up with intention in daily life. Whatever tool will help you, find it, and use it.

A year-and-a-half after my clown trip, I clown less often than before. But when I feel the itch, I put on my clown clothes and nose, to remind myself to show up with joy, and to promote connection.

Clowning has taught me that no matter where I live, whether it’s Hawaii, Buffalo, or NYC, I can choose to be a tree. I can choose to provide shade, nourishment, and beauty for those around me.

That’s what clowning has taught me.

What I loved about our DIY wedding

You must invent your own religion, or else it will mean nothing to you. You must follow the religion of your fathers, or else you will lose it. –Hasidic Proverb

Today, we got legally married. About a month ago, we had our DIY-style backyard wedding ceremony.

I just erased a white-board full of things we could have done better with the event. While it’s good to learn from shortcomings, it’s also good to savor what went well.

In this spirit, here’s a list of things I loved about our wedding:

- The generosity of our hosts for a million and one acts of love and service.

- Dancing the hora and stilt-walking the day after (thanks Hallie).

- The beauty of the decorations: candles, shots, tables, lighting, flowers (thank you friends who set these up, and Sonia-space creator and Api-designer)

- The cultural remix of Thai (white thread bracelets, Khan Mak), Jewish (glass breaking, Kittel, music) and Clown elements.

- My dad’s joy on the dance floor.

- Api’s mom and dad joy

- Letting the organism of the event flow in the way it wanted to flow (thank you to Pat for stepping up and MC-ing, and thanks Nicole/Lisa for the advice to let go).

- The food, makeup, photographer, florist (thanks Mama for help finding many of these folks).

- The bachelor gathering (some highlights: cacao, Nicolette’s voice, softing, rock-climbing hike, Nicole’s game).

- Opening the gifts with both our families. My favorite gift: David’s home-brewed bottle of alcohol that sent me back down memory lane. Thank you notes are in-production!

- The speeches. Thank you everyone who gave one.

- The shots of vodka.

- Elements from both our lives: my violin teacher Max, videos of Api’s friends from Thailand…

- Family time at our house, the day before and after (thanks Mama and Papa for creating such a warm vibe).

- Our first dance.

- Glowsticks!

- Everyone who gave moral support in the months leading up to the wedding (especially: Peter, Avi and Ethan).

- Reading the poem praise the rain, as it rained, while serving tea, with the fireplace crackling.

- Being scared to invite certain folks and then having them actually be really supportive.

- Josh stepping up as audio-visual wizard.

- Overcoming a whole host of challenges: getting COVID, redoing the seating chart, food/dessert issues, cold and rainy weather, losing track of many props, glasses that arrived dirty from the rental company…

- The music (thank you Young Picassos).

- My dad’s chupa, and plum trees.

- Traveling after the wedding: with the in-laws to Canandaigua and Canada for a post-bachelor party.

- Not having shoulds: starting with a blank piece of paper and including the elements from our cultures and lives that resonated with us.

- People showing up, traveling from far away, to attend.

- The support and love I felt from everyone there.

- Scenius: the collective genius of many individuals providing their gifts to make the beautiful tapestry of the event what it was.

- The love vibration in the tent. This was probably the most important thing, for all of the above would be moot if this wasn’t there.

The interbeing of apples

The gray sky

I used to think

Was just the grey sky

The winter cold

Just the winter cold

But as I bite into an apple

This October

I see that in order

For this apple to be

The grey sky

And winter cold

Must be,

Too

The movie is always playing

Right now

Wonder wander is happening

Nicole is going to NYC

And I'm drinking tea

Doing none of the above

Pursuing the social, novel and exciting

To the exclusion of rest

Leads to burnout

An overstuffed sandwich

The movie is always playing

Learn to take breaks

To process

What you've seen

Cefdinir

One day shy of 95

My grandma

Fell ill

I held her, thready pulse

Do you want to go to the hospital?

No.

So, was this it?

Shaky and eyes closed

Was this it?

Quality of life over quantity

The mantra goes

Easy to accept

In the abstract

The last few weeks

Quality was not that good

A lack of purpose

Had set in

Taken care of

Not taking care

Unwanted attention given

To cleanliness

Down there

My mom

Knew exactly what was wrong

When she saw her

And knew

Exactly what she needed:

Cefdinir

A sufficiently advanced technology

Is indistinguishable from magic

Another mantra goes

Thanks to cefdinir

My grandma turned 95

Gratitude can be

For tragedies

Narrowly averted

It's good

To pause and stop

To say:

Thank you cefdinir

Philosophy of time

On a plane yesterday, I read most of the book 4,000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman. This book that helped me realize that I don’t have a practical philosophy of how to spend my time. Sure, I abstractly knew that how we spend our time is of central importance to living a “good life.” Yet I didn’t have a practical way to apply this insight to the choices I make every day.

The metaphor from the book that I keep coming back to is that of rocks in a jar. The rest of this post will further develop this metaphor.

The rock jar metaphor

The rock jar metaphor goes like this:

- The jar of our life is of a limited size.

- We humans have unlimited imaginations and can think of thousands of possible rocks for our jar: different and varied careers, places to live, people to spend our time with.

- Realizing this, we get to choose which rocks we put in our jar, and which rocks we leave out of our jar.

This metaphor is useful because I have a tendency to deny my jar’s limited size. Saying no to things I’m drawn to is inherently painful. So is admitting my mortality.